The Vortex of Ezra Pound & Charles Olson

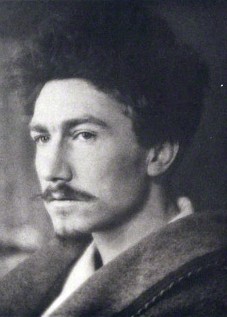

Ezra Pound photographed as a young man in 1913 by Alvin Langdon Coburn

THE VORTEX of EZRA POUND & CHARLES OLSON

by Cary Loren, 2005

I guess the definition of a lunatic is a man surrounded by them. – Ezra Pound

POUND AS TEACHER

The poet Ezra Pound (1885-1972) had been an early pioneer and proponent of the “Free University” – and as early as 1914, Pound dreamed of starting his own academy. In a letter to Harriet Weaver[i] in 1914, he wrote “…it was to be a college of the arts,” and he set forth the curriculum: “That the arts INCLUDING poetry and literature, should be taught by artists, by practicing artists not by sterile professors… the arts should be gathered together for the purpose of inter-enlightenment… the art school, meaning ‘paint school’ needs literature for backbone, ditto the music academy, etc.,” Failing to get his arts college, Pound set about constructing an “academy by mail,” a forerunner to the network of free universities. Pound once said, “It takes about 600 people to make a civilization.”[ii]

Pound was a teacher of great dimension. Each of his books, especially Guide to Kulcher, were written for a small audience of scholars. He found meaning by reaching out to other artists and poets—those who would fulfill his dream of academy: a strategy that was uniquely his own and worked. As the world became refreshed with new movements in art; fauvism, Dadaism, post-impressionism, futurism, etc., Pound found himself the architect of two; Imagism a poetry movement and Vorticism, a movement primarily of the visual arts; painting, drawing, photography and sculpture.

Pound’s pedagogy is covered in James Laughlin’s[iii] warm memoir of the poet; Pound As Wuz, where Laughlin examined Pound’s teaching methods that included; parody, networks, manifestos, reviews, translations, anthologies, prose books including artist biographies and massive letter writing. Laughlin points to Pound’s great personal epic and most famous work The Cantos, as being an extended teaching aid, 117 cantos in almost 800 pages, “written out of a prodigious memory”[iv] and modeled after the epics of Homer and Dante.

As an educational tool, The Cantos, with its woven texts in 13 languages, is a modern enigma: its mysterious density with references to history, philosophy, myth, religion, economics, and the teachings of Confucian China are pasted together in fragments and variations, image upon image, as the poem is treated like pasted collage, puzzle, or musical fugue. The modernism that Pound is given credit for is centered on fragmentation and collage, an influence that extended deep into the visual arts.

Ernest Francisco Fenollosa, (1833-1908)

Pound was the first modern poet to include references, history and commentary, all woven inside the fabric of the poem itself. The Cantos, can be viewed as a model for many of the great modernist epics including; T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland, The Bridge by Hart Crane, Paterson by William Carlos Williams, A by Louis Zukofsky, Charles Olson’s Maximus Poems, Ginsberg’s Howl or Plutonium Ode, d.a. levy’s North American Book of the Dead. By reaching into the ancient past, Pound was able to bypass most of the nineteenth century baggage affecting language. He looked for new land and direction—a cosmos that was free of the past but still included it. Pound himself mined the Cantos for his series of Radio Plays and experiments with music and technology in the 1930s.

Pound made a landmark discovery, changing the course of his life in 1908 when he discovered Ernest Fenollosa’s[v] book, The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry, a book where Pound opened up to the kinetic properties and “vivid shorthand” of the Chinese ideogram, which he would transpose into western poetry. Pound was an amateur translator of Chinese ideograms, but used his poetic intuitive sense to arrive at their meaning.

Fenollosa’s essay would have an even deeper influence on the aesthetics of Pound, who saw it as a doorway to unlock meaning in the arts. The ideograms had meaning beyond language and logic: a visual language dealing in fragmentation, leaps of thought and connections that may be illogical or out of order. The ideogram was an ancient doorway to the modern world.

Fenollosa described the general exhaustion that had developed in western poetry–how contemporary poetry had disconnected itself from the primacy of ancient language. As Fenollosa’s literary executor, Pound published his books Cathay (1915), Certain Noble Plays of Japan (1916), and Noh (1917). But Pound delayed publishing The Chinese Written Character until 1958, long after he mined it for usefulness.

Pound was oblique and dismissive in acknowledging Fenollosa: “It is not as if Chinese was Fenollosa’s discovery.”[vi]This idea was articulated in Pound’s book How to Read and would be used and expanded by his disciple, Olson within his essay ‘Projective Verse.’ This was not the first instance of a poetic theory being transferred from one language (or the art form of calligraphy and music) into another, but it does connect ‘Projective Verse’ theory; breath reading, and the abstract arrangement of the page back to its ancient source, and shows how Pound unlocked a new pathway toward his goal of always making it new.

Pound’s influence on modernism is unquestioned, but the problem of Pound’s intersection with the visual arts is still partly unresolved. It’s certain that James McNeill Whistler left a deep impression on Pound, probably less so for his painting style (which he greatly admired), as for his bohemian attitude and style. In 1905, Pound began signing his poems with a gadfly in imitation of Whistler’s butterfly signature. “Whistler was ‘our only great [American] artist. He, Ezra Pound was going to ‘carry into American poetry the same sort of life and intensity which [Whistler] infused into modern painting’ Whistler seemed a sort of modern troubadour, an outcast for Art’s sake’ a Bohemian dandy whose clothes Ezra began to copy – the best model he could think of at present.”[vii]

Whistler was a prime advertisement of bohemian style and dandyism; a figure who represented the smashing of traditions, a new Baudelaire. In his poem; To Whistler American[viii], Pound expresses his own desires in transforming the American cultural landscape, by his example, he ‘had tried all ways’ which gave to Pound the ‘heart to play the game.’ The molding of a new expression and reform in art is called to those ‘Who bear the brunt of our America, And try to wrench her impulse on Art’. – here Pound sees that the trials of the artist are linked to an indifferent and dumb America which could produce a [Whistler] ‘and Abe Lincoln from that mass of dolts’ and by those examples (and Pound’s too) ‘Show us there’s chance at least of winning through’. To Whistler, American appeared in the first issue of Poetry (October, 1912), a landmark magazine started by Harriet Monroe, the future champion of James Joyce, in which Pound is listed as foreign correspondent on the masthead.[ix]

From his association with Wyndham Lewis, in London, Pound announced the platform of VORTICISM—a movement that drew attention to its close proximity to Cubism and Futurism. First announced in their arts journal Blast #1, of 1914, Pound’s manifesto ‘Vortex’ wished to distance Vorticism from Futurism: “We (the Vorticists) do not desire to evade comparison with the past. We prefer that the comparison be made by some intelligent person whose idea of ‘the tradition’ is not limited by the conventional taste of four or five centuries and one continent… Futurism is the disgorging spray of a vortex with no drive behind it, DISPERSAL…EVERY CONCEPT EVERY EMOTION PRESENTS ITSELF TO THE VIVID CONCIOUSNESS IN SOME PRIMARY FORM. IT BELONGS TO THE ART OF THIS FORM. IF SOUND, MUISC; IF FORMED WORDS, TO LITERATURE; THE IMAGE, TO POETRY; FORM, TO DESIGN; COLOUR IN POSITION, TO PAINTING; FORM OR DESIGN IN THREE PLANES, TO SCULPTURE; MOVEMENT TO THE DANCE OR TO THE RHYTHM OF MUSIC OR OF VERSES…. Dispersed arts HAD a vortex. Impressionism, Futurism, which is only an accelerated sort of Impressionism, DENY the vortex. They are CORPSES OF VORTCIES. POPULAR BELIEFS, movements, etc., are the CORPSES OF VORTICES. Marinetti is a corpse.”[x] By calling Marinetti (and Futurism) a corpse, Pound and Lewis were positioning themselves as a unique movement, and not just the second act of Futurism. Its unfortunate that Vorticism has been lost under the dust-balls of history. There exist fine examples of cross-disciplined art that is rooted in Pound’s vortex—an idea too esoteric for its time.

Pound’s manifesto grants visual art a kind of energy and rhythm closely associated to music. His own Imagist movement in poetry: ‘the primary pigment of poetry is the IMAGE’ was folded into the new language of Vorticism: ‘The vortex is the point of maximum energy. It represents in mechanics the greatest efficiency…. All experience rushes into this vortex. All the energized past, all the past that is living and worthy to live.’ Pound continues to define the vortex and which arts would play a major role: sculpture, dance, music and verse. Photography would also link with Vorticism through the work of Alvin Langdon Coburn, who encouraged by Pound would invent and produce Vortographs, perhaps the first intentional abstractions in photography.

Guide to Kulchur by Ezra Pound, New Directions, 1938

Pound’s university-in-a-can was the Guide to Kulchar (1938). Called a manual, road map, tour guide and “Baedeker of culture” – Pound aimed his Guide to Kulcher at the general reader; an uneducated audience that could absorb his “iconoclastic revision of the cultural curriculum”[xi] at ground level. Pound points the reader and seeker to various texts and systems of knowledge, pulling the student in a specific direction; “Certain books form a treasure, a basis, once read they will serve you the rest of your life.”[xii] He covered much of the same territory in the Cantos, but Kulchar being a series of interconnected essays is presented in a much more compact and digestible form.

OLSON AS STUDENT

After WW II, Pound was set to stand trial for treason by the United States government for his Anti-American, pro-fascist radio broadcasts made from Italy. The penalty for this crime was death. However, Pound was judged to be “too insane to stand trail” and in 1945, was incarcerated in the mental wards at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington D. C.

Charles Olson was covering Pound’s trial for Dorothy Norman’s[xiii] Twice-A-Year magazine (a literary journal deeply influenced by Alfred Stieglitz), and was among his first visitors. At the time of that first visit, Olson was being considered for an important cabinet position in the government, either assistant to the Secretary of the Treasury, or as postmaster general of the United States; both well-paid insider positions within Truman’s administration.

Olson’s first intention was to try and save Pound from a looming death penalty, which many thought he’d receive. “Olson felt compelled to “save the scoundrel’s skin”… In truth, Olson was torn; the New Dealer in him detested Pound’s political attitudes, but he was dazzled by Pound’s poetry, and perhaps even more affected by the energetic, aggressive authority of the literary and cultural criticism.

Reading Pound’s prose, Olson felt at once challenged, intimidated, provoked and awed. In his journals, Pound had become a sparring partner, pervading his mind with a shadow presence that went beyond mere influence. Olson wrote, “Should you not best him?” he goaded himself. “Is his form not inevitable enough to be used as your own? Let yourself be derivative for a bit… Write as the fathers to be the father.”[xiv] Olson kept up his visits and developed a deep involvement with Pound. Energized by their discussions, he soon wrote off his career in government, and dived head long into the poetic abyss.

Olson continued visits to the prison for two-and-a-half years, and with his impeccable memory, he wrote extensive notes after each session. These would not be published until long after both their deaths in the book: Charles Olson and Ezra Pound: An Encounter at St. Elizabeths. During that time, Olson was forming his personal mythos and techniques. He had not yet been a published poet, yet his mentorship with Pound was life-changing. Olson took up a serious study of Pound’s sources and influences, eventually joining a small circle of Pound’s close friends and disciples called “the New Company” – it was there that Olson began to first read in public, arranging the spoken word in relation to music (via Greek choral music). This was a proposal made by Pound, whose motto was Walter Pater’s statement that all the arts approach a condition of music.

Olson was frustrated with the Pound enigma. He wrote, “In Pound I am confronted by the tragic Double of our day. He is the demonstration of our duality. In language and form he is as forward, as much the revolutionist as Lenin. But in social, economic and political action he is as retrogressive as the Czar.”[xv] Slowly, Olson broke off this relationship, clearly at odds with Pound’s fascist and anti-Semitic ideology, saying, “All he wants is the purring and tears of fellow fascists… Poor, poor Pound, the great gift, the true intellectual, rotting away, being confined and maltreated by the Administration. SHIT. And he is taken in by it! Here he’s punk like the rest of them.”[xvi]

Olson’s first book was a powerful critical analysis on Herman Melville titled Call Me Ishmael, written during his prison visits with Pound. Olson’s great themes can be found in the ultra-individualist, anarchist and transcendentalist style of Melville—and through the line connecting Melville to Pound and himself. For Olson, Melville and Pound represented the frontier of American society, and Moby Dick was a primal confrontation of industry and wilderness. WHALE = SPACE, was Olson’s poetic equation of the enormous openness, and soon-to-be-exploited western-lands of Melville’s era.

At the heart of Olson’s text was a rejection of post-War American values. A value system em>closed down to the expanse of human awareness, that stood in opposition to the natural world: a rejection of metaphysical ideals that could help restore lost primal energies. For Olson, Melville represented that lost wilderness, the unexplored physical and mental states of a youthful unknown space: America at its birth. Olson was probing that connection at mid-century, and became part of a radical change in culture. He exploited the cracks in the tissues of learning, contrasted between societal goals, government programs and the contrary doctrines adopted by avant-garde artists. Olson’s influence on the ’50s and ’60s was monumental in poetic and philosophic progress. The great shadow of Melville was cast over Olson.

“Is it that by its indefiniteness it shadows forth the heartless voids and immensities of the universe, and thus stabs us from behind with the thought of annihilation, when beholding the white depths of the milky way?” –Herman Melville, Moby Dick

Listen to Ezra Pound’s readings at PENN Sound.

Notes:

[i] Harriet Weaver was the co-publisher of the New Freewoman along with Rebecca West and Dora Madson, Pound was an editor at the paper which published his Imagisme works. As New Freewoman began publishing more of Pound’s circle he convinced them to change its name and it became the Egoist and was the first to publish James Joyce, serializing Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

[ii] James Laughlin quoting Ezra Pound in Pound As Wuz, (Greywolf Press, St. Paul, MN, 1985) pp. 41-42.

[iii] James Laughlin was the publisher of New Directions, one of the first avant-garde presses in America focused on poetry.

[iv] Pound As Wuz, p.107.

[v] Ernest Fenollosa was a the leading expert on Asian art, and a close friend to Charles Lang Freer.

[vi] Ezra Pound, Guide to Kulchur, (New Directions, 1938) p. 313. Fenollosa was the Imperial Commissioner of Art in Japan, a station at the University of Tokyo. In 1906 he was buried in a classic Japanese ceremony (attended by Charles Freer) at Midera, a temple in Otsu overlooking Lake Biwa, where his memorial temple still stands.

[vii] Humphrey Carpenter, A Serious Character: The Life of Ezra Pound (Houghton Miflin, Boston, 1988) p. 63.

[viii] Ezra Pound, Poems and Translations (Viking, NY) p. 608.

[ix] A Serious Character: The Life of Ezra Pound, chap. 8 p. 176-195 covers the years 1912-1913 as foreign correspondent for Poetry.

[x] Ezra Pound, Ezra Pound and the Visual Arts,Ed., Harriet Zinnes (New Directions, 1980) p.151-152.

[xi] Guide to Kuture, publisher’s back cover blurb.

[xii] Guide to Kulchur, p. 312.

[xiii] Dorthy Norman was a photographer, assistant, protégé and mistress to Alfred Stieglitz. Twice-A-Year began as literary extension of an American Place, the gallery run by Stieglitz and Norman.

[xiv] Tom Clark, Charles Olson: The Allegory of a Poet’s Life (North Atlantic Books, 2000) pp. 98-99.

[xv] Charles Olson, Catherine Seelye, Charles Olson & Ezra Pound: An Encounter at St. Elizabeths (University of Connecticut, 1975) p. 53.

[xvi] Humphry Carpenter, A Serious Character: The Life of Ezra Pound, ( Houghton Miflin, Boston, 1988) see the chapter “Hell-hole” on Pound’s imprisonment, pp. 725-741.

Tags: Cary Loren, Charles Olson, Ernest Fenollosa, essay, Ezra Pound