Monteith College: Roots of the Workshop

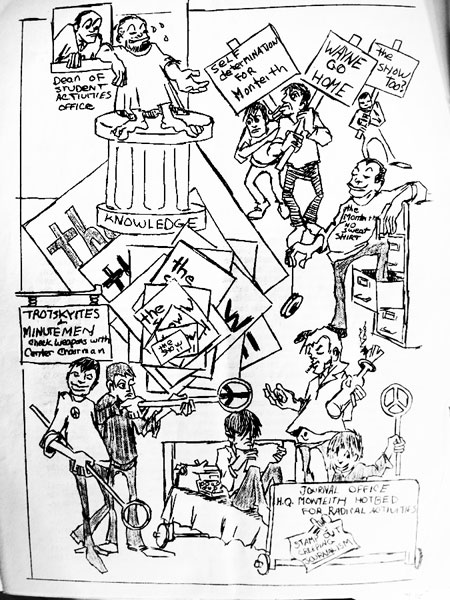

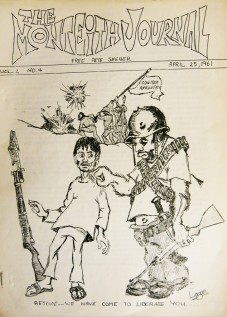

Monteith Journal cartoon by Chuck Logan, 1961, Vol 4 April 2, 1962, editor Chuck Logan

Leni Sinclair found part time work assisting professor Otto Feinstein, a mentor and early supporter of the Artists Workshop. Feinstein arrived in Detroit in 1960, from the University of Chicago, where he was an outspoken activist, humanist, organizer and early founder of the anti-nuclear movement. Feinstein came to teach at the newly opened (1959) small collage of Monteith, located inside the campus at Wayne State University. Monteith was an alternative college with small classrooms. Its first graduating class had 313 students; the area code for Detroit. Feinstein described the college as having “an emphasis on acquiring the art of dialogue—that is, on expression and communication of ideas orally and in writing, with peers and professors.”[i]

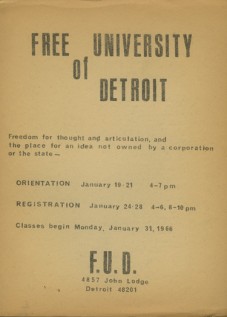

A Holocaust survivor and fervent anti-fascist, Feinstein was also the founding editor of New University Thought [NUT] in 1959—one of the most influential left-wing journals of its day. NUT published and supported student-run political groups; its major currents were civil rights, peace studies and student movements—it encouraged activism, democracy, unity and community. NUT asked, “Can one work in the shadow of death? Can one love in the ashes of Hiroshima?”[ii] It published radical experimental works—including a reprint of the second Artist Workshop manifesto. Feinstein encouraged participation, a belief in community. He said, “…one of the most common features of the present period is a practically subconscious fear of structure, organization, and form…. We are thus struck with a great dilemma which must consume a significant portion of our mental energies – how to unite our community, without ourselves participating in the dehumanization which has given the copyright of the word “individual” to its most basic enemies, the bureaucrats.”[iii][1] Feinstein had boundless energy—a life-source he transferred to students and associates, planting many seeds to transform the community. Encouraged by Feinstein, on November 1st, 1961, Leni went to Chicago as part of a nationwide ban on anti-nuclear testing. The protest was partially organized by Women Strike for Peace, an anti-nuke group founded by Bella Abzug and Dagmar Wilson—among the first Women’s groups in the United States opposed to the war in Vietnam.

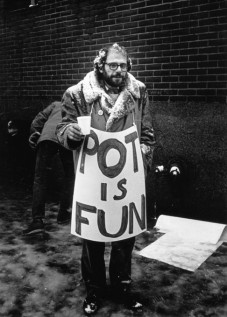

Leni said, “I went on my first ‘peace march’ in 1961 to Chicago with a friend I had at Monteith who wasn’t a student or faculty—his job was called “a participant observer”. Because Monteith had been this experiment from sociology professors from Chicago—they paid one guy to be the observer, to watch and write everything down; interactions between students, who hangs out with who, what they do, and how they do it. We were never in the peace movement—we were just so far outside that whole thing, but thought of ourselves as more radical and political—we were totally outside of it. We followed LeRoi Jones, Malcolm X and Archie Shepp; those were the real radicals… and we saw the peace movement as bourgeois… We found out one of the top leaders of the Movement to End the War in Vietnam, was also working at the Warren tank plant—I mean, how can you be political after five o’clock? —We weren’t playing a game—we just lived it full time!”

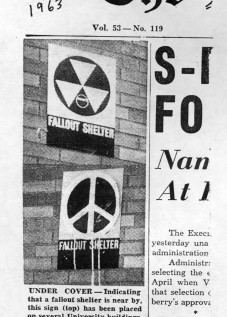

As Feinstein’s assistant, Leni kept the subscriber rolls for New University Thought, sent out mail, and ran errands, keeping the office running smoothly and organized. Although not enrolled at Monteith, Leni spent most of her time there and at the student center. While a first year student, Leni created her first public protest: an altered graffiti sign. By adding paint strokes to a nuclear fallout sign, she was able to change it into a peace sign—forcing signs of capitalism and fear against themselves, a practice known as detournement. The student paper The Collegian Daily and the Monteith Journal both picked up on Leni’s anonymous handiwork, publishing them on their front pages.

Front cover of The Daily Collegian, WSU student paper; Fallout Shelter changed into Peace Sign (with expressionist drips).

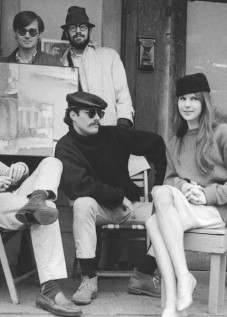

Otto and other Monteith professors converted an old Edwardian house on Second Street into a student hang out. Monteith and WSU poets and artists gathered there and formed a loose framework in the early ’60s for the future AWS; Robin Eichleay, George Tysh, Doug Larkins, Charles Moore, Chuck Logan, Timothy Phalen and Ellen Phalen. The student center became a place to gather and discuss ideas. A mimeograph machine was set up in the house, where students collaborated on the Montieth Journal, a student run literary journal. Robin Eichleay and George Tysh were editors at the time. The professors at Monteith encouraged student democracy and activism, keeping them supplied with paper and mimeograph equipment. The formative stages of the Artist Workshop Press is directly traced to the Monteith Journal.

Leni described these nascent beginnings of the AWS press; “…it ended up that in the last couple issues of the Monteith Journal, almost all the people who wrote for it, who had poetry in it, later on appeared in Work Magazine [AWS press]. The incubation happened at the student center. So we utilized the mimeograph machine and published our first magazines and books by running them off late at night, ream-by-ream, cranking—no, it was electric, it wasn’t hand-cranked. Then after a while we bought our own mimeograph machine and learned how to do it well, and we learned where we could get stencils from, how we could put photographs in it. Then we also got a stencil burning machine so we could do those. And then we refined the art of mimeographing and sometimes we made flyers in two and three colors. That means you have to change the ink on the machine after the first run and then the second run is with a different color ink. But the covers—we usually managed to get enough money together to get the covers printed by offset by some printer. Then eventually—the Artists’ Workshop Press published these magazines. We also got into printing small booklets of poetry. There were about twenty issues before it fizzled out.”[iv]

Monteith Journal, Vol.2 #4, April 25, 1961, George Tysh, editor. Cuban invasion cartoon by Chuck Logan

Poet George Tysh first met Leni while she was assisting Feinstein and at the student center. George said, “Otto was a real important guy for me; I first met Leni through Otto. We’d hang out at the Monteith student center. We did all kinds of shit there… we smoked dope – they had sex there… kids would find little corners and hook up – but it wasn’t that common. There was mostly card games going on.”[v] George was an editor at the journal and almost thrown out of school several times –once for running a subversive cover. He said, “there was a drawing on this one cover of a Montieth journal that had a muscular marine on it, grabbing a peasant by the shirt – Chuck Logan drew this – and it said; “we have come here to liberate you” – a response to the Bay of Pigs invasion. The shit hit the fan on that!—a well known conservative alumnus got ahold of it and freaked out… he told the school board to get rid of the creeps putting this out.”[vi]

The Montieth Journal mimeo press published a mixture of poetry, essays, short stories, editorials, humor and occasional drawings. Ellen Phalen, Leni Sinclair, Robin Eicjele,

[i] Montieth College Archives Collection, papers 1959-1972 introduction by Dean Yates Haefner

[ii] Editorial, New University Thought, Special Issue, Peace, Spring, 1962

[iii] Otto Feinstein, ‘Is There a Student Movement’ in New University Thought V.1, No. 4, Summer, 1961, Chicago, p. 28-29. Feinstein was a member of the “Committee on Social Thought” at the University of Chicago in the late 1950s, where Hanna Arndt would later teach and become a full-time professor. Feinstein wrote early papers on the determent of Atomic nuclear expansion. He was a major organizer and figure in the anti-war movement, and founded the Detroit Wayne State journal New University Thought. At his Eulogy and Memorial service held in January, 2004, attended by Leni Sinclair and myself, Feinstein’s close friend Eric Bockstael stated, “His experience of and fight against Nazism and fascism is really what drove Otto.. He told us many times that it is that experience and impatience with the adults of the time that brought him to start the school-to-school project and the youth/urban agenda, to give kids a voice, to prepare them to act politically in their respective societies. Kids, he said, are not the generation X, the social and political lazybones, and idlers. It is the institutions not responding to nor creating opportunities for kids that are the generation x, the slackers.”

[iv] Fitzgerald, Michael. “A Bibliography of Change magazine.” Current Research in Jazz 1, (2009). Leni Sinclair, Telephone interview, December 30, 2009. http://www.crj-online.org/v1/CRJ-Change.php

[v] Conversation with George Tysh 8/11/13

[vi] Conversation with George Tysh 8/11/13

Note: this is an excerpt from Panic in Detroit a work in progress by Cary Loren on photographer Leni Sinclair

Tags: Cary Loren, Essays, George Tysh, Leni Sinclair, Monteith, Otto Feinstein, WSU