Allen Ginsberg: Poet of Peace

ALLEN GINSBERG: PEACE POET

ALLEN GINSBERG: PEACE POET

In 1967, Allen Ginsberg made a visit to Ezra Pound in Italy and discussed the important link between the “Master of Modern” and the beat generation. Michael Reck wrote up this special occasion in a summer 1968 issue of Evergreen; “Ginsberg leaned over to Pound and said, ‘Your thoughts about specific perception and (William Carlos) William’s ‘no idea but in things’ have been a great help to me and many young poets. And the phrasing of your poems has had a very concrete value for me as reference points for my own perception… in your work, the sequence of verbal images, phrases like “tin flash in he sun dazzle” and “soap-smooth stone posts” – these have given me, in praxis of perception, ground to walk on…

Pound responded to Ginsberg’s declaration saying, ‘A Lot of double talk.. My writing. Stupid and Ignorant all the way through. Stupid and Ignorant.’

Ginsberg said, ‘You have shown us the way, the more I read your poetry, the more I am convinced it is the best of its time. And your economics are right. We see it more and more in Vietnam. You showed us who’s making a profit out of war… ‘

‘Any good I’ve done has been spoiled by bad intentions – the preoccupation with irrelevant and stupid things,’ Pound replied. And then very slowly, with emphasis, surely conscious of Ginsberg’s being Jewish: ‘But the worst mistake I made was that stupid, suburban prejudice of anti-Semitism.’

‘Its lovely to hear you say that,’ said Ginsberg. Whereupon he added: ‘Well no, because anyone with any sense can see it as a humour, in that sense part of the drama, a model of your consciousness. Anti-Semitism is your fuck-up… but its part of the model… it’s a mind like everybody’s mind…. Ginsberg continued, ‘What I came here for was to give you my blessing… I’m a Buddhist Jew whose perceptions have been strengthened but the series o practical exact language models scattered throughout the Cantos like stepping stones, because, whatever your intentions, their practical effect has been to clarify my perceptions. Do you accept my blessing?’

The Master hesitated, opened his mouth a moment, and then the words appeared, ‘I do.”[i]

Pound’s admission to his mistake was a large move on his part that went widely unnoticed. His guilt over fascism and anti-Semitism unfortunately colored his work as worthless or largely ignored—a shame since he was a giant of modernism and a direct link to Olson and the Beats.

Ginsberg made many pilgrimages to other living authors who inspired him and his fellow writers. He was instrumental in bringing notice of William Blake to a new generation of readers. He recorded Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience, a surprisingly popular album. This was Ginsberg’s way of teaching and acknowledging the contribution of poets from the past to the contemporary canon. He was a constant teacher, turning on readers, reading other poets work—keeping alive many important, over-looked writers.

While living at the notorious “Beat Hotel” in the late 1950s, Ginsberg, Burroughs and Corso made contact with the surrealists through Jean-Jacques Lebel at a party at his father’s house. Andre Breton, Man Ray, Tristan Tzara and Marcel Duchamp were there—a meetings across generations which ended in an embarrassing drunken stupor for the young Americans. “The first thing goddam Allen does, he gets down on his knees and kisses Duchamp’s knees . Thinking he was doing something surrealistic. And Duchamp was so embarrassed… he was trying to do something Dadaistic. The most embarrassing thing was yet to come. Gregory had found in the kitchen a pair of scissors, and he cuts Duchamps tie…actually Duchamp loved the guys and Man Ray loved the guys. Every time I’d see them they’d say, “Where are your American beatniks? I love these beatniks.”[ii]

At a meeting with Céline, both Ginsberg and Burroughs were threatened by his “Jew hating” German Shepherds. They presented Céline with freshly published American versions of Junkie, Howl and Gasoline, explaining how they were all influenced by his writing. After their departure, they looked back and noticed Céline dispatching their books into a garbage can.

Ginsberg met with the writer Henri Michaux, whose voyages with mescaline were an inspiration for the beats. Ginsberg helped create the chain of drug investigations between generations of the twentieth century. Allen Ginsberg: “He had a new book out called Moments – M-O-M-E-N-T-S – … and they were just moments on different drugs, including ritalin (one on hashish, one on ritalin, one on mescaline). So he gave me the book and showed me which experiment was with which drug. (He) says he doesn’t take too much any more because he’s getting old – too wearing. He was recently involved with a lot.. with nitrous oxide and (with) ether. He got interested in that… later.. for the first time.”

Ginsberg was a life-line for fellow beat writers, offering encouragement, money, finding publishers and negotiating contracts for William S. Burroughs, Gregory Corso and others. A powerful teacher, his outspoken attacks on the ‘military industrial complex’ was stand up. He brought Blakean guidance and a humor tinged Zen approach in all things human.

Ginsberg along with Anne Waldman founded the ‘Naropa Institute” and the ‘Jack Kerouac School for Disembodied Poetics’; a University of Denver, Colorado retreat. Begun in 1972, the school was modeled after the Free University movement and attracted young writers to its summer sessions of workshops and seminars. It is still in operation: NAROPA UNIVERSITY

Ginsberg was a liberating force. Beyond his poetry and language, his attitude toward sexuality, drugs, love and freedom were inspirational—they were expressions he kept naked and in public view, freedom lessons all could learn from.

‘Howl’ has become the most-quoted standard of the beat generation. Ginsberg used the media attention to his advantage. His portrait was a best-selling poster. He pooled his energy into celebrating and defending personal freedoms: in addressing the inequality of drug laws, fighting police brutality, racial inequality, opposing greed and counter-intelligence activities of the C.I.A.—activity that drew him closer into the limelight and gave him a public forum. His public friendships and collaborations with Bob Dylan and John Lennon led many to discover his work –and helped radicalize other culture barons.

This public pedagogy was similar to Pound’s technique: he used his books and speeches to attract a select elite of students. They in turn became a schoolhouse of turned-on youth that spread this small circle of poets and writers to a wider audience.

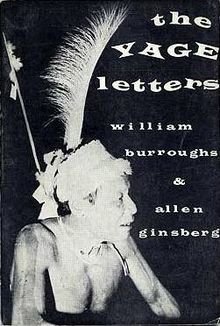

The publication of Yage Letters (1960) with William S. Burroughs, was an important volume linking drug culture to world culture, spirituality and anthropology. A slight book, it helped guide the ‘60s explorations in drug cultures—an adventure that was connected worldwide. Contemporary youth-migrations to Katmandu, Morocco, and Goa, became linked with Eastern spiritual journeys; one Ginsberg helped create.

Ginsberg continued his chronicle of these explorations and journeys in the Great Marijuana Hoax (1966), Planet Dreams (1967),Airplane Dreams (1968), Ankor Wat 1968, and Indian Journals (1970). Ginsberg’s attack on the hypocrisy of American drug laws was a four-decade long struggle. He assembled one of the finest libraries on drugs and drug-use in the nation—and used that knowledge to help change laws and give witness to the hypocrisy of the criminalization of marijuana.

“I believe that future generations will have to rely on new faculties of awareness, rather than on the versions of old idea-systems, to cope with the increasing godlike complexity of our planetary civilization, with its overpopulation, its threat of atomic annihilation, its centralized network of abstract word-image communication, its power to leave the earth. A new consciousness, or new awareness, will evolve to meet a changed ecological environment.” –Allen Ginsberg, The Great Marijuana Hoax, Atlantic Monthly

In the introduction to Ginsberg’s selected essays: Deliberate Prose, poet Ed Sanders noted, “The message, complicated and lifelong, was one of reacting to suppression and oppression through insistent nonviolent action, candor, openness, and love. He was like a bacchic/ bardic/ Buddhaic/ Judaic Gandhi in that regard… Allen Ginsberg made it his business to know the intricacies of his nation, more so than any bard in our history… He loved to teach. If he opened the refrigerator door, he gave a lecture on the rice milk and organic food on the shelves.”[iii]

In Ginsberg’s essay ‘Outline of Un-American Activities’ first published in The Writer and Human Rights (Doubleday, 1983) he discussed his relationship with Sinclair and the Artists Workshop:

“In Detroit there is a rock and Jazz Impresario named John Sinclair, who was a poet much beloved by Charles Olson. In 1965, we had a big poetry meeting in Berkeley, and Ed Sanders, Anne Waldman and John Sinclair were invited specifically by Olson to represent the younger generation. Sinclair had an organization in Detroit called the Artists’ Workshop, which published huge mimeographed volumes of local poetry, as well as pamphlets by correspondents. He put out a long anti-communist manifesto (Prose Contributions to the Cuban Revolution) that I wrote in 1960 about the Cuban Revolution, a sort of challenge to the spiritual foundations of it saying that it was too materialistic. So he wasn’t exactly a riotous red. His main thing though, his main “shtick,” so to speak, was uniting black and white in the otherwise tense, riot-torn areas of Detroit, through the Artists’ Workshop, because there was collaboration between black jazz musicians and white jazz musicians, black writers and white writers, black poets and white poets. It was a kind of heroic effort, actually.”[iv]

Ginsberg came to rally support for the Artists Workshop many times. His efforts on behalf of the Free John Now campaign were instrumental in helping bring justice to the case. In the film Ten for Two: The John Sinclair Freedom Rally, Ginsberg opens the ceremony with a ritual chant on his harmonium:

“O dear john Sinclair we pray you leave your jail house/ o dear John Sinclair we celebrate your liberty tonight / o dear John Sinclair in your name we are having a paarty/ fourteen thousand people here – with no fear..” – Allen sweetly intoned.

It was Ginsberg’s legacy to lift poetry up; to give it a home beyond the walls of academia. To make it live. His voice and rebel attitude had a peaceful tone. He taught meditation and non-violence at every chance. Ginsberg was the beat image of resistance, peace and flower-power incarnate. He helped educate his audience to awareness. His poems and gentle nature grace the sixties landscape; forever set as the major poet of his time. A poet for peace.

–Cary Loren, 2005

[i] Michael Reck, ‘A Conversation between Ezra Pound and Allen Ginsberg’, Evergreen, June, 1968.

[ii] Jean-Jacques Lebel quoted in Barry Miles, The Beat Hotel: Ginsberg, Burroughs and Corso in Paris 1958-1963 (Grove Press, NY, 2001) p.125-126

[iii] Ed Sanders in introduction to Allen Ginsberg, Deliberate Prose: Selected Essays 1952-1995 (HarperCollins, 2000) pp. xxi-xxiii.

[iv] Allen Ginsberg, Deliberate Prose: Selected Essays 1952-1995 (HarperCollins, 2000) p.40.

Tags: Allen Ginsberg, Cary Loren, Essays, Poetry