Arthur Interviews John Sinclair

Exit interview with JOHN SINCLAIR (2003)

Originally published in Arthur No. 6 [Sept 2003], available from the Arthur Store….

“Everything is worse than ever”

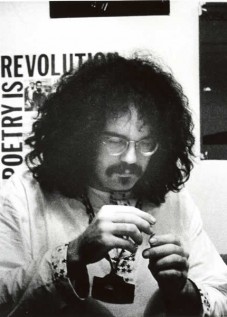

A conversation with righteous MC5 manager/poet/scholar/activator and great American JOHN SINCLAIR, who is leaving the country

Introduction by Byron Coley

John Sinclair casts a huge shadow across the American underground. The force of his personality and energy of his vision kept the midwest alive for several years. His writings, howlings and example ignited fires in the brains of kids everywhere, and his return to live performance in the last few years has been a cause for elation.

Sinclair was born in Flint, Michigan in 1941. His father worked building Buicks. John would have followed his footsteps had he not been driven mad by hearing R&B. The music—so alive, foreign, transformational—clicked a switch and he was never the same. In high school John became a party DJ and record nut. After graduation, he found affinity with words, especially those of Charles Olson and the beats. He dropped out of college after two years, getting heavily into jazz, writing poetry and doing drugs. Newly illuminated, Sinclair finished his BA, and began graduate studies.

John’s high profile drew lotsa heat. He was busted for pot in 1964, again in 1965. Shifting his wheels out of the academic rut, along with his partner Leni, John founded the Artists Workshop—a collective involved in publishing, presenting readings, film showings and concerts. He also wrote about high energy music for Downbeat and elsewhere. After Cecil Taylor played him the Beatles’ Revolver LP, Sinclair made the pivotal decision to get back into rock music.

Busted again in 1967, John began a long legal odyssey. At this time, the Artists Workshop transmuted into Trans-Love Energies, and he began working with a young band called the MC5. By filling their brains with righteous dope, free-jazz and politics, a quintet that might have been remembered as the American Troggs was transformed into the pinnacle of free-rock perfection. In 1968, the tribe moved to Ann Arbor and the White Panther Party was founded. The Panthers’ stated goal (revolution via rock and roll, dope and fucking in the streets) seems a bit naive now, but at the time it sounded perfect.

By upping his political content, Sinclair got deeper into shit. After producing the first Detroit Rock & Roll Revival in 1969, he got 10 years for having given a nark two joints. Sinclair continued to write from prison (mostly politically charged music criticism). This work was collected into the essential Guitar Army. [Guitar Army was reissued by Process Media in 2007: http://processmediainc.com] The MC5 couldn’t handle his imprisonment, however, and left Trans Love (at the behest of future Springsteen slave, Jon Landau). Fortunately, others took up his cause. There were numerous benefits, culminating in a massive Detroit rally, featuring John & Yoko, Archie Shepp, Stevie Wonder, Phil Ochs, Bob Seger, the Up and Ed Sanders. In 1971 the case was tossed out.

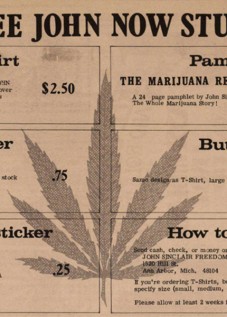

Sinclair continued to mix politics and music, although the Panthers were folded into the Rainbow People’s Party (a less obstinately provocative organization). A full time political activist, Sinclair lobbied for marijuana reform, involved himself in community work and put together the Ann Arbor Blues & Jazz Festivals. Sinclair also had a book of poetry published in 1988, at which time he returned to the live stage. But by 1991, local politics had bogged him down and he headed south to New Orleans.

Sinclair continued to do radio shows, edit magazines, write about music, and do wild-ass performances of investigative jazz poetry. He formed a band called the Blues Scholars, and recorded explosively syncopated albums of music and words. He also rekindled his friendship with former MC5 guitarist, Wayne Kramer, which resulted in excellent new work, fantastic archival releases and the promise of much more of both. His latest book is a blues suite Fattening Frogs for Snakes and many future projects beckon.

Hearing through the underground grapevine that Sinclair was preparing to exit America, Arthur arranged a phoner with the great man. The following Q & A was conducted by Jay Babcock in July [2003].

ARTHUR: So you’re leaving America.

JOHN SINCLAIR: Yes, God willing.

ARTHUR: And you’re going to…?

SINCLAIR: Amsterdam. I have a patron there and they said if I came over they would take care of me until they could get me set up and then I could call for my wife. That’s an offer I’ve been waiting for all my life. Now I’m old and I can really use it. [laughs] I wanna get the hell out of here. [laughs]

ARTHUR: You’ve been traveling around the last couple of months, so you’ve been getting a good look at the mood of the country. And you can remember when the resistance to the Viet Nam war was starting. Is the current situation—the state of the country now—worse than it was back then?

SINCLAIR: Oh yeah. The people are so much dumber now. They’re just…painfully dumb. They love this guy Bush, they love all this stuff that’s going on, and they’re gonna return him to office in a big way, and it’s gonna get worse and worse. That’s what I see. And except for the occasional glimmer of light like that new issue of Arthur, [laughs] it’s hard to even find people who have any inkling of what they’re doing.

ARTHUR: How did Americans get so dumb?

SINCLAIR: Well, television, movies, pop music. You know, they’ve just surrounded them for the last 30 years with this horseshit. And they’ve destroyed their critical faculties. And they give them things. The white people, they give them everything. And so they’re happy. They’ve got their big cars, they have lots of money and the smugness of feeling like it isn’t affirmative action for white people that’s making this happen. [sarcastic] It’s because of their brilliance, their savoir faire.

ARTHUR: Is the education system in this country really worse now than it was in the ‘50s or ‘60s?

SINCLAIR: Oh yeah… Everything is worse than ever. [Jay laughs.] Well it is! I mean, I grew up in a little country town outside of Flint, Michigan. My dad worked for Buick Motors in Flint for 43 years. Back then the schools had this phony obeisance for the arts. The arts were your out. When I discovered poetry and writing and Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg and then Charles Olsen and Robert Creeley and Leroi Jones and people like that, that was the LIFELINE. And the music. You could hear good music on the radio. All of a sudden there was Little Richard. There was Chuck Berry. There was Muddy Waters. In your bedroom. And they were just like little arrows pointing you in another direction. They weren’t like anything in your experience. It was so much better. [laughs] It was so far superior. It gave you a lifeline to something that was interesting.

ARTHUR: Drugs like marijuana and LSD were coming into popular use…

SINCLAIR: You got that from the music, and the records. Otherwise you would’ve just thought it was some horrible thing that was gonna kill you, you know. But the musicians were open about it—it was clear they were getting high and they were making this great music. You had these really dynamic things like the Beatles, which was like the Backstreet Boys or something, and all of a sudden they dropped some acid. Bob Dylan turned em on to weed. And Allen Ginsberg had turned him on to weed. You know what I’m saying? [laughs] I mean, there’s a line, and then all of a sudden, it exploded! And then you had Sergeant Pepper, which you know, really pushed boundaries in every direction and really brought the idea of intelligence into the music, which was always there in any kind of African-American music, but white pop music had always prided itself on its vapidity. Pat Boone. Elvis after he went in the Army. [laughs] It gave you all this feeling that, you know, maybe something’s going to happen. Something IS happening.

You know, I spent 50 years in Michigan. I turned 50 like three months after I got to New Orleans. I’ll be 62 in October, unbelievably. What I like about getting old is that I never pictured it. I have no template, I have no expectations except I think I’ve lived long enough to now want to get some recognition for what I did in my lifetime, which I never cared about while I was doing it. [chuckles] I just wanted to DO IT. And had a ball!

ARTHUR: That’s one of my favorite bits from Guitar Army, the constant emphasis that “We are having the best time, we know how to have the best time, and they’re trying to take it away from us.”

SINCLAIR: We were having a ball. You only had to look around: any fool could see these other people were miserable. As we had been—before we got turned on. I don’t know what to think about the future, or what young people are gonna do now. I just hope they get to where we got, to where you just couldn’t stand it. [laughs] We were ahistorical! We had no idea about the labor movements of the ‘30s or the commies or the HUAC or any of that shit. You just didn’t know anything about anything. Because even then the education system was terrible…

You know, Orwell’s 1984 is such a beautiful model for what they’re doing. There’s this ‘two different worlds’ part of it: the world ruled by Big Brother, which is the middle-class white people or the other kinds of ethnicities seeking to be white, and they’re in this totally controlled world where they’re watching and making sure there’s no deviance from the prescribed norm. But then if you step out of that and you go the ghetto, like Winston Smith–he goes to the ghetto and lays up with some homegirl, you know. You can get high. Anything goes, as long as you don’t cross the paths of the police—they’re really just to keep everyone in the ghetto. They don’t care so much what you do. I mean, the crack epidemic was the ultimate truth of that. So there was neglect–or encouragement. In Detroit, it turned out the police were making big money off of it. You’d turn down a street and five people would run up to your car, trying to sell you some drugs. I said geez in my day if you stepped off a corner and tried to sell some drugs you’d be gone in five minutes…

ARTHUR: How do you view Guitar Army now? Is it just an artifact? A document of the times? Or is there something more there…?

SINCLAIR: It’s completely stamped with the time, which is the thing I think gives it whatever value it has. As a document of the times, it’s extremely accurate. However, so many of the ideas were proved to be so full of shit, you know…

ARTHUR: What things were proved to be full of shit?

SINCLAIR: [laughs] The basic premise: that youth is a class.

ARTHUR: When did you realize that?

SINCLAIR: When the Eagles began their ascendancy. Fleetwood Mac. “Tommy.” I mean, when popular music turned from something that had an edge to something that was just sappy. They bought the artists, and then they surrounded the People with the bought-off artists. Basically. That’s the way I saw it. They BOUGHT them. And then these people became incredible millionaires. But no one did anything interesting with it! There was a handful of people, the Jackson Brownes, the Concert for Bangladesh — you know, people wanted to do something, but basically they bought ranches in Venezuela. They bought rainforests. They became General Motors.

ARTHUR: Was that inevitable, or was it a lost opportunity?

SINCLAIR: Well that’s the kind of stuff I don’t know anything about. All I can do is look at what happened. I don’t know why. If I did, I would be wealthy probably! [laughs]

ARTHUR: In Guitar Army, you talked about living communally, about living and working outside of a capitalist framework, that sort of thing. Do you still think that’s a real possibility? Or was it just a delusion of that era?

SINCLAIR: Well, I think we can do it on our own but I don’t think it’s gonna have any societal effect. You see what we thought then was if we did this enough, and enough people got into it, eventually we would transform the greater reality. And I can’t see that now. I practice the things I believe in because they bring me pleasure and joy, despite the grinding poverty. But it’s like, Don’t try this at home unless you’re ready for a lot of ugliness. [laughs]

ARTHUR: Once you take the vow of poverty, anything is possible.

SINCLAIR: Right! Because you can do whatever you want to, beyond pay your rent. [laughs] That’s the hard part. But conceptually, mentally, imaginatively, creatively, you can do whatever you want to. The sad thing is so few want to do anything. Boy oh boy, it’s so frightening. When you’re in Europe, you look over… I’m a newspaper fiend. So you read the International Herald Tribune, and even that tells you more about what’s going on than the New York Times, for example. And past the New York Times, you get to a Detroit Free Press or a Los Angeles Times or a San Francisco Chronicle, they’re so awful. They don’t tell you anything about what’s going on. They’re just propaganda mechanisms. So people watch this and they say Well yeah this is fairness. They talk about the ‘liberal media.’ There are no liberal media. They don’t even have a liberal talk show. The people in this country are docile. They LIKE it.

I was enjoying David Byrne’s diaries [in Arthur 5], the way he said so many of his friends were just parroting back this propaganda at him. That’s the part that frightens one the most. You expect Bush, Cheney, Richard Armey, Tom DeLay and all of these kind of Newt Gingrich-type people to be the way they are, and to do the things they’re doing, but you don’t expect everyone to think that it’s great. I’m not old enough to have experienced the rise of the Third Reich, but I can’t help but imagine it was very much like this. When you had the war coverage, the Operation Enduring Freedom in Iraq, all that kind of stuff, and it made you think, they must have had great human interest stories about the S. S. troops and their brave wives and families that were waiting for them at home as they swept off to Czechslovakia. [laughs]

ARTHUR: Why are Europeans viewing the present situation so differently?

SINCLAIR: They’re so much more intelligent.

ARTHUR: Is it down to some sort of critical thinking skills that they’re taught in school?

SINCLAIR: I think there’s some of that. Also they teach them history. And they treasure the Arts. See, the arts here, the arts are like toilet paper here. They’re something to wipe their ass with. There’s no premium on the arts. They HATE the arts. The schools, they don’t teach you about the arts. And then the arts the people are into are so unartful. Ha! The things they think are great. And then you’ve got a generation or two of postmodernist theory, which is so totally full of shit, which starts with the premise ‘there is no more history.’ Well, HORSESHIT. This is history now! They’re making history. They’re doing things they’ve never done before in America! They’re just declaring they’re gonna go and kick people’s ass and take their stuff. It’s just thuggery! And everyone else in the world see this and they go for it or they’re opposed to it, but they know what it is. Whereas here, it’s cloaked in this noble rhetoric, that we’re liberating the poor Iraqi people and the women in Afghanistan. It really is just naked grabbing of assets. It’s the most ignoble thing I’ve ever seen in my life.

ARTHUR: Do you see similarities with the way the war in Viet Nam started?

SINCLAIR: Yeah they kind of eased into and then, well, it’s the same thing as the Gulf of Tonkin, these ‘weapons of mass destruction.’ There was no incident at the Gulf of Tonkin, yet all but one person in Congress voted to have war because of this incident that didn’t occur.

ARTHUR: Is the only way this thing is gonna end if there’s a revulsion about the number of American soldiers being killed…?

SINCLAIR: I don’t know how it’ll end, Jay, I don’t have any idea. It’s all so unprecedented. I’m just afraid when people wake up and really start to try to deal with this that it’s going to be very brutal, the response. Cuz they’ve got every… See, we surprised them in the Sixties. [laughs] You know what I mean? They didn’t see any of that coming. They thought Vietnam would go down like Korea had gone down: an ‘inescapable and important police action to save the world from the spread of Communism.’ And instead all of a sudden there were thousands and then hundreds of thousands and then millions of people protesting this. And the people who were in favor of the war were kind of just grimly plodding forward doing their duty–they weren’t really proud. See, these people are proud now. They’re kickin’ ass. [laughs] Everything’s all lined up. In the government, everything’s lined up. And then the people that the government serves, who own the corporations and own the media, it’s all lined up against us. [laughs] That’s the way I look at it.

ARTHUR: That’s why the word ‘fascism’ starts to crop up, cuz that’s–

SINCLAIR: That’s exactly what it is: unity of government, industry and the banks. And no one is doing better right now than the banks. Because they had that deficit down, you see? The banks can’t make any money without a deficit. So now they’ve got the biggest deficit of all time! So that means they’re just shoveling millions and billions of dollars into the banks in interest. I haven’t read my paper yet today, but maybe they’ve taken the prime rate down to 1/2 or 3/4 of a percent. Can you imagine how much money they’re making on that? To buy money for half a percent and sell it to you…for, you know, whatever. If it’s a credit card company they’re selling it to you for 29%! I mean, those are UNBELIEVABLE profits. And then the things they caught all these corporations doing in terms of bilking their investors and their workers and everybody to aggrandize themselves personally. The Enron model: the 5,793 offshore corporations controlled by the treasurer? You know. [laughs] I mean, this shit is serious. They’re completely re-organizing our society. And as an artist, you know, you see things like the cast of Friends gets a million dollars per week per episode. Each of them. And you think, man, I just got evicted. [laughs] I’ve been an artist 40 years.

ARTHUR: So basically your attitude is ‘Good riddance.’

SINCLAIR: Well… my attitude is W-H-E-W-exclamation point. If I make it. I’ve still got work here to do in the States, that’s why I’m planning to go in November. I’ve got work through the end of October.

ARTHUR: What are you gonna miss about being in America?

SINCLAIR: Well, my thousands of friends. I miss New Orleans already. I’ve already left New Orleans cuz I figured it would take me several months to get over that. New Orleans is the most American city because they’ve got all the music. The thing I love about New Orleans the most is music is part of life. It’s all authentic music with roots in blues and jazz and gospel. It’s part of everyday life, part of the people’s rituals. It’s not all about getting a record contract and getting rich. Although you have your Master P and Cash Money and all that ugly shit…

ARTHUR: What’s happened to black culture in this country?

SINCLAIR: Ohhhhh… That’s an awful topic. You see, that’s the ugliest thing about America today for me is that most black people have never heard a good record. Most of them alive today, especially young people, they don’t know who Muddy Waters is. They don’t know who John Coltrane is. They don’t even make music anymore. You know, they have this horrible rhythm and blues, they call it. And then they have the hip-hop and rap and the gangsters — the ‘New Minstrelsy’ is what I call it. Threatening white people for money. I don’t know. I’m a white person, so I’m not qualified, really, to give any kind of critique, you know?

ARTHUR: Yeah but… It’s a sad state of affairs. The African influence in America, which has always been one of the saving graces of this nation, seems almost completely gone.

SINCLAIR: Yeah. The beautiful thing was it showed you how to make a life even though they didn’t want you to have one. I mean that’s the inspiration of African-American music. Blues. You took these people who were subjected to the worst treatment of anyone except the Natives, maybe even worse, cuz they just took everything from the Natives, but they didn’t make them plow the fields and pick cotton. They did move ‘em around quite a bit, ‘Trail of Tears.’ But this is what’s great about New Orleans, it’s still like that there! The most downtrodden people have the most fun. [laughs] They devise celebratory music and public rituals in which anyone can take part whether you have a dime or not. And you can just blow your brains out and have the time of your fuckin’ life, day after day, week after week, year after year. Even though you don’t know how to read and write. I mean, there’s a lot to be said for that. [laughs] Well it helps inspire people like us who are trying to do something different, who have rejected our privileges, in a way.

ARTHUR: The brass bands down there are amazing: the Rebirth Brass Band–

SINCLAIR: Anywhere else than New Orleans these guys would be looked upon as… sissies or a joke or something. Extremely corny. But in New Orleans, they’re just out there on the street! Or in a bar. They don’t have a microphone. They’re completely mobile. They’re a musical guerilla unit. They show up, set up, anywhere, and within two minutes they’re just blasting this greatest music ever made by humans. For four or five hours, or whatever is required. It’s the greatest!

I like New Orleans because… well, it’s old, it doesn’t have any industry or anything to recommend it. [laughs] No Fortune 500 companies are based there. But that’s a matter of much chagrin to the upper middle class and of course they’re trying to change it all the time. They’re pretty aggressive right now. They got a reform mayor, a businessman. They wanna put the fuckin’ city on a “business-like basis,” and you say, Well Jesus Christ that’s what’s ruined everything else in our country! [laughs] Who wants a “business-like basis”? You mean, cut those staff, give the rich people more money? Degrade the products? I dunno, I thought Burroughs put his finger on the whole thing about 45 years ago when he said that consumer society is about simplifying and degrading the consumer as well as the product. I think that’s what we’ve seen since you know, 1963. For sure. Probably 1950. Since the CIA took over.

ARTHUR: Why don’t more people embrace this music, or this way of making music, outside of New Orleans? Is it all down to the lack of respect for the arts, like you were saying? No budget for arts education, etc.—

SINCLAIR: Oh yeah. They don’t teach music anymore. You see… Look at be-bop. Be-bop came out of these black kids getting access to world-class music training in the public schools that was designed for white kids, in the ‘30s and ‘40s, even into the ‘50s. Detroit produced so many outstanding jazz musicians—just a whole generation of incredible artistry. And so in the ‘60s, they cut the music programs out of the schools. And there you go. So next thing they’re playing on turntables. That’s what’s left for them. Oh man. The more I talk about it, the more depressed I get. [laughs] I just try not to think about it in daily life. I mean, you’re aware of it all the time but if you don’t really train your thoughts on it, you don’t get depressed.

ARTHUR: I’m curious about what you’re reading and listening to these days…

SINCLAIR: I think the best writing today is in crime fiction. [laughs] I like Elmore Leonard and James Lee Burke, Carl Hiaasen. I love James Ellroy—man, he’s about my favorite. Cuz he deals with the shit.

And what I listen to is blues. Modern records: Magic Slim and the Teardrops, Super Chicken, you know these totally demented guys. RL Burnside, I played with one of his sons the other night. [laughs] I’ve shunned pop music for about 30 years. Since the Eagles came up. Jesus Christ.

ARTHUR: So you had no interest in the punk movement?

SINCLAIR: No. It didn’t sound very good and really they didn’t have anything… I mean, they just wanted to get rich too, really. Only they wanted to do it by not learning how to play! [laughs] Ah, you know, I’m just an old curmudgeon, Jay. But I’m sitting here in the beautiful Mississippi sunshine, and it’s a lovely day.

Tags: Arthur Magazine, Byron Coley, Interviews, John Sinclair