John Sinclair Interview: Turning People On

Turning People On

Turning People On

The following is an excerpt from a conversation between Dave Brinks and John Sinclair which took place on the evening of Saturday, February 28, 2009 above the Gold Mine Saloon in the French Quarter, New Orleans]

Brinks: There’s about eight hundred things I’ve always wanted to ask you, but one thing that really jumps into my head, as we were talking about poet Robert Creeley a minute ago, and as Creeley was putting together that book of poetry by Paul Blackburn, which was made after Paul died, called Against the Silences, and how Creeley was thinking of Paul’s documentary efforts of course, and his poetry, and how all that’s just one bag, and in the preface to that book, Creeley states “It’s a very real life. The honor, then, is that one live it.”

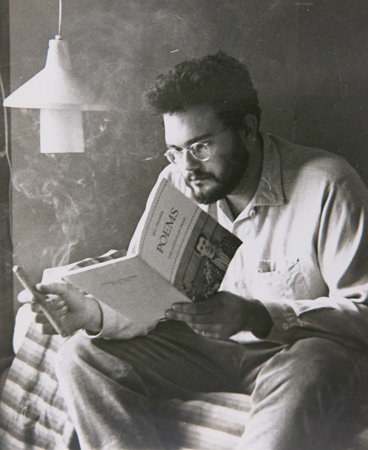

So, that’s pretty heavy, right, but then in 1964, you’re 23 yrs old, and on November 1st you founded the Detroit Artists Workshop, and about six months later you’re headed off to the now legendary Berkeley Poetry Conference of July 1965 where Ginsberg introduces you there as one of four “Young American Poets,” and in great company, with poets Ed Sanders, Ted Berrigan, and Lenore Kandel; and you bring fresh-off-the-press copies with you of that first issue of your magazine Work, and your first book This Is Our Music-so my question is two words actually, aside from everything , and still today, because the conversation continues: why poetry?

Sinclair: I’ll say it like Lenny Bruce said it, “Why not?” Lenny would say, Why use narcotics? Why not? I don’t know man, I mean, poetry-Allen Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti, those were the first ones I read, and Kerouac’s prose where poets were glorified, and I mean, the idea of being a poet was not something that was out there on the table, you had to find that one.

And that’s probably the same question my mother had, “Why poetry?” John, couldn’t you just write some songs or something you might get paid for? No, mom, you don’t understand. But it was a noble cause. You felt these guys, once Ginsberg and Ferlinghetti had City Lights Books going, waving the flag, they were there-they got these little books out, they were like 75 cents, there was Kora in Hell by William Carlos Williams, there was Gasoline by Gregory Corso, Paroles by Jacques Prévert, I can see those things, and Howl, Kaddish, Pictures of the Gone World, they were just fucking perfect: Iconically, textually, visually.

Yeah, they put poetry-it wasn’t like Robert Frost, or these cornballs I couldn’t stand-it was a manly endeavor. These guys were also hanging out at night clubs with black people, listening to jazz, or smoking marijuana, following these narcotics addicts like Charlie Parker. It was just so appealing. And I got it listening to jazz right exactly at the same time. It came as a package to me.

It was life in a different part of the social order from anything that had been proposed. They were actually creating poetry readings where they had a lot of fun. Fucking unbelievable, with Gary Snyder reading from what would become Riprap, and Michael McClure reading his incredible odes. That was just very, very attractive to me.

And the more you looked into to it, the more you found. And then you get to Charles Olson and Robert Creeley. And that was the twin towers, real poetry. Not to say Ginsberg isn’t real poetry because he is. But I mean Charles Olson is real poetry man, and he’s a real poet. That was his identity and that was what he did.

And the idea of that was overwhelming, that you would be a poet, and what would you do-you would write poems, and you would study it, and you would learn about things you were interested in, and then your poems would say what you had to say.

And they would also provide thrills-rhythmic and intellectual and emotive thrills, ya know. It was like an R & B record, or a Soul record, but it was heavier in a way. It was farther out. It didn’t rhyme. And there wasn’t anyone who was going to play it on the radio. You had to type up stencils and run them off the mimeograph machine to disseminate these works. Those times were so exciting to pursue.

Brinks: I’d like to talk about your magazine Work and those early days, and also the whole idea of that title Work, but specifically in the Creeley aspect of things, that work is something that happens between people; and also with the knowledge of humanness which comes specifically from Olson’s thinking.

Sinclair: It was also an exhortative: You work. It was a way of life. It was a concept that we were committed to. And this stuff was work, it wasn’t just bullshit, it wasn’t frivolous-I mean writing, it’s work. And the Detroit Artists Workshop was where you did the work. And you did it together in a communal setting, or in a cooperative setting that was communal at best; and we also lived together, so we had to do that too.

And like I said before we started, we sealed our fate in a way, and stated our intention, when we put the notice on our publications: COPYRIGHT IS OBSOLETE. We really believed that. And part of it was, ya know, there wasn’t really any concept that you would ever be compensated for this. That was part of the work-that you would do this work, despite the fact that unlike regular work, you wouldn’t get paid, and it would be its own reward.

And you would turn people on, not so much to your works, but to a concept of work that they could adopt and give meaning to their lives. That was the exciting part-not so much that someone was reading one of your poems, although of course this gave you a certain satisfaction to get a response from an audience. But it was really about the whole experience, and everybody involved, and the fact that we were making something in life in America that wasn’t like what it was supposed to be. It wasn’t about money, it wasn’t about ego, it wasn’t about career advancement. It was about doing the work, and doing it together, and having fun doing it, making it happen-that was fun shit.

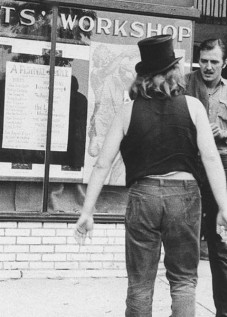

Jerry Younkins (back), Allen VanNewKirk (facing), other person unidentified, in front of Artists Workshop (on John Lodge) 1966 (?)

We did poetry readings every Sunday. We were like second-lines in New Orleans. On Sunday afternoon you went to the Artists Workshop, then there was a poetry reading, and some musicians played, and whatever books you had, you would bring, like Allen Ginsberg or Amiri Baraka (who went by LeRoi Jones at the time) and Diane di Prima-people who were your role models. You would want to have their books so the other people could have access to this, so they could be as elated by it as you were.

Turning people on was the core value of our whole thing really. We wanted to turn people on. We just wanted to turn ’em on to art, poetry, and jazz. Then we started taking acid, ya know-regularly, and in groups. And then you developed this messianic feeling: you wanted to turn everyone on to everything. And you’d say, man, this works, you know, you might really like to try this. What a trip that was.

You see, we were so far out on the edge of the social order. And in those days at the Artists Workshop, we had already basically written off the idea that any regular people could get to any of this. We felt that the only people who were really qualified to accept and enjoy this work were people who had already made some sort of commitment to a bohemian approach to life.

We used to run our own flyers off for our Sunday afternoon Artists Workshop events. We’d stand on the corner on the campus of Wayne State, and we’d only give them to people who had moustaches. You wanted to get people that were coming out of the same matrix as yourself, because maybe they would get some of this, and at the very least, they would have a good time with it ’cause they weren’t looking for-I don’t know, the Beach Boys. We were on a search and destroy mission, ha ha. I guess it’s arrogant in a way, but I mean, arrogance was probably a big part of our epic ambiguity.

Source: The online poetry zine: Big Bridge

Tags: Interview, John Sinclair