Alice Coltrane: Enduring Love

The music is within your heart, your soul, your spirit, and this is all I did when I sat at piano. I just go within. –Alice Coltrane, Jan 16, 2007 NPR Interview

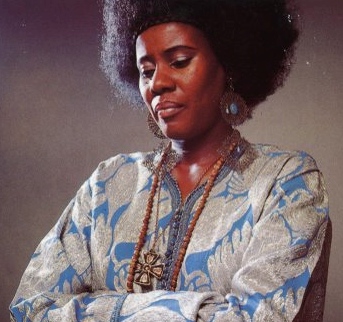

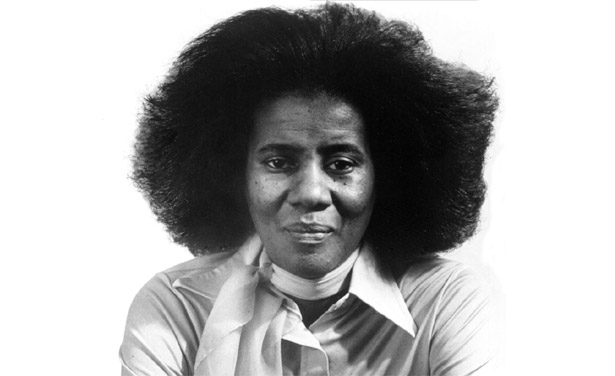

Alice Coltrane was an uncompromising pianist, composer and bandleader, who spent the majority of her life seeking spiritually in both music and her private life. Music ran in Alice Coltrane’s family; her older brother was bassist Ernie Farrow, who in the ’50s and ’60s played in the bands of Barry Harris, Stan Getz, Terry Gibbs, and especially Yusef Lateef. Alice McLeod began studying classical music at the age of seven. She attended Detroit’s Cass Technical High School with pianist Hugh Lawson and drummer Earl Williams. As a young woman she played in church and was a fine bebop pianist in the bands of such local musicians as Lateef and Kenny Burrell. McLeod traveled to Paris in 1959 to study with Bud Powell. She met John Coltrane while touring and recording with Gibbs around 1962-1963; she married the saxophonist in 1965, and joined his band — replacing McCoy Tyner — one year later. Alice stayed with John’s band until his death in 1967; on his albums Live at the Village Vanguard Again! and Concert in Japan, her playing is characterized by rhythmically ambiguous arpeggios and a pulsing thickness of texture.

Alice Coltrane was an uncompromising pianist, composer and bandleader, who spent the majority of her life seeking spiritually in both music and her private life. Music ran in Alice Coltrane’s family; her older brother was bassist Ernie Farrow, who in the ’50s and ’60s played in the bands of Barry Harris, Stan Getz, Terry Gibbs, and especially Yusef Lateef. Alice McLeod began studying classical music at the age of seven. She attended Detroit’s Cass Technical High School with pianist Hugh Lawson and drummer Earl Williams. As a young woman she played in church and was a fine bebop pianist in the bands of such local musicians as Lateef and Kenny Burrell. McLeod traveled to Paris in 1959 to study with Bud Powell. She met John Coltrane while touring and recording with Gibbs around 1962-1963; she married the saxophonist in 1965, and joined his band — replacing McCoy Tyner — one year later. Alice stayed with John’s band until his death in 1967; on his albums Live at the Village Vanguard Again! and Concert in Japan, her playing is characterized by rhythmically ambiguous arpeggios and a pulsing thickness of texture.

A Monastic Trio Subsequently, she formed her own bands with players such as Pharoah Sanders, Joe Henderson, Frank Lowe, Carlos Ward, Rashied Ali, Archie Shepp, and Jimmy Garrison. In addition to the piano, Alice also played harp and Wurlitzer organ. She led a series of groups and recorded fairly often for Impulse, including the celebrated albums Monastic Trio, Journey in Satchidananda, Universal Consciousness, and World Galaxy. She then moved to Warner Brothers, where she released albums such as Transcendence, Eternity, and her double live opus Transfiguration in 1978.

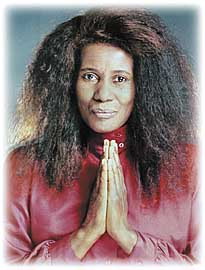

Long concerned with spiritual matters, Coltrane founded a center for Eastern spiritual study called the Vedanta Center in 1975. Also, she began a long hiatus from public or recorded performance, though her 1981 appearance on Marian McPartland’s Piano Jazz radio series was released by Jazz Alliance. In 1987, she led a quartet that included her sons Ravi and Oran in a John Coltrane tribute concert at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City. Coltrane returned to public performance in 1998 at a Town Hall Concert with Ravi and again at Joe’s Pub in Manhattan in 2002.

Long concerned with spiritual matters, Coltrane founded a center for Eastern spiritual study called the Vedanta Center in 1975. Also, she began a long hiatus from public or recorded performance, though her 1981 appearance on Marian McPartland’s Piano Jazz radio series was released by Jazz Alliance. In 1987, she led a quartet that included her sons Ravi and Oran in a John Coltrane tribute concert at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City. Coltrane returned to public performance in 1998 at a Town Hall Concert with Ravi and again at Joe’s Pub in Manhattan in 2002.

Translinear Light She began recording again in 2000 and eventually issued the stellar Translinear Light on the Verve label in 2004. Produced by Ravi, it featured Coltrane on piano, organ, and synthesizer, in a host of playing situations with luminary collaborators that included not only her sons, but also Charlie Haden, Jack DeJohnette, Jeff “Tain” Watts, and James Genus. After the release of Translinear Light, she began playing live more frequently, including a date in Paris shortly after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and a brief tour in fall 2006 with Ravi. Coltrane died on January 12, 2007, of respiratory failure at Los Angeles’ West Hills Hospital and Medical Center. Source: Chris Kelsey, All Music

Divine music is one of the highest mercies extended to us by God. It is as powerful as prayer itself. The potency of sacred music has in certain instances superceded the curative properties of medicine, mantra, and affirmations. This is due to the heart’s principle of love, purity, and innate receptivity. Often, the mind that knows the use of recitation and affirmations, at times has found that little value results when it exhaustedly abandons the constant repetition.

Divine music is a curative virtue; it is a gift from God that brings healing and comfort to the soul. This music can uplift one’s spirit up to a higher dimension of being that is filled with peace and joy. Divine music is the sound of true life, wisdom, and bliss. This music transcends geographical boundaries, language barriers, age factors; and whether educated or uneducated, it reaches deep into the heart and soul, sacred and holy, like an Infinite sound of glory entering the Lord’s sanctuary. –Swamini Turiyasangitananda

Alice Coltrane — the jazz pianist, organist and composer who was the second wife of John Coltrane — was a devotee of Indian guru Sathya Sai Baba. In the early 1970s, she established the Vedantic Center, changed her name to Turiyasangitananda, and became the swamini (spiritual director) of an ashram in Malibu. She continued to compose music, releasing numerous recordings of spiritual jazz, chants, and swinging devotional songs. Much of this was available only on cassette via the ashram’s Avatar Book Institute (and later CD). Last year, perhaps the most stunning cassette from this period, Divine Songs, was reissued on vinyl. First released in 1987, Divine Songs consists of nine deeply soulful, trancey, and moody tracks expressing her deep Hindu influence. Turiyasangitananda sings and plays her signature 70s Wurlitzer Centura organ with accompaniment from her ashram students. Source: David Pescovitz, Boing Boing

Wire Magazine Interview with Alice Coltrane, June 2004

The Wire: Were you introduced to the piano through playing the instrument in church?

Alice Coltrane: “Basically yes, although there was a neighbour that lived in our building who was a music teacher and I asked her (I was very young, I was about seven years old), if she would give me piano lessons and she agreed.”

Alice Coltrane: “Basically yes, although there was a neighbour that lived in our building who was a music teacher and I asked her (I was very young, I was about seven years old), if she would give me piano lessons and she agreed.”

Was this how you first became interested in playing music?

“From the age of seven I had basic classical music training through the teacher. I was being taught European classical music, theory and harmony. I had no exposure, technically, with any indigenous music or music of our country such as jazz or gospel. I had not come to that point with music.”

What did you learn from playing this music?

“An appreciation for their music. It certainly was a great learning experience for me. I still admire classical music today and I think every pianist should have some classical background because there were so many excellent pianists from the European culture. I think it would prove to be an asset to learn from them.”

How did you get involved with playing jazz music?

“That was through a family member, my eldest brother Eddie Farrow. He had already begun his career by playing bass violin and he was very well known in our city of Detroit. I thought he inspired me quite a bit to play jazz music. I don’t think there was any earlier influence on me other than my brother.”

Did you hear any other players at this time?

“I heard them, but I think he was the inspiration and motivation to really get involved.”

Before that you met Bud Powell in Paris. Was he a hero of yours?

“I would think so. He was so excellent, just so skilful and creative with his music.”

Was it at this point that you decided to become a serious musician?

“I think it was more of a resolve to really continue because I had already started. Little musical events would occur around Detroit, for example, I would play for weddings, funerals, and I would play at the Elk’s Lodge, so I had some experience. But when I went to Europe and I met Bud Powell over there, I think I just became more resolved, more determined in my resolve to continue.”

Paris and Detroit must have seen like a world away at the time…

“It was. In terms of Europe I think my interest came when I knew that a lot of youngsters were involved in an exchange program. European students would come to America and study here for a while American students would also go to Europe and study the culture, history, music and art. So that sort of sparked an interest in me to go, because I knew I would see a lot of youngsters from the USA and it would be nice.”

How did the trio come together?

“The trio? It would have to be something that was made up from Detroit. A lot of times my own brother was on the job or people I knew. They would call me and say, ‘Are you working? We need a pianist’. I did have a few jobs in New York with Johnny Griffin the piano player, and after him I’m pretty certain it was Terry.”

How did you meet Terry Gibbs and how did you become a member of his band?

“Basically my brother recommended me, because he was in his band and Terry didn’t have a pianist, so my brother mentioned me to him. So I said to my brother, OK, If you think so, fine. So that’s how I started working there. We ended up recording four albums together.”

One of them being Terry Gibbs Plays Jewish Melodies In Jazztime…

“That was funny, but it was a good album. Terry is very humorous and comedic and he keeps you laughing, but he is also a person who is very serious about his music, and that I could appreciate from him.”

You also played vibes in his band?

“He had a certain routine. He and one of my friends Terry Pollard – who is also from Detroit and she was a good friend of my brother and a little older than myself, so I looked up to her like a sister – and they had such a fine performance on the vibes between themselves. It made headlines in magazines and there were really nice write ups about it, and they’d call her the Queen Of The Vibes at the time. We were very proud of her, because she was really good.”

Did Terry introduce you to John?

“He’ll tell his version, but it really did transpire through the fact that we were coming in from California on our way to New York. While we were driving there I asked Terry who else was on the show with us. He said, ‘I don’t know, maybe John Coltrane I’m not sure’. So I said, Oh good, I hope it is John Coltrane. When we reached New York and spent one or two nights seeing him back stage I found him to be a very quiet man and so much into his own deep thought that I felt very reluctant to even say anything to him. Maybe we were close to ending a week, we just sort of gradually spoke a few words here and there. But when you look at someone like that and you can see like a profound inner, kind of ground that he always appeared to be in, you don’t wish to disturb that. After awhile we found that we shared a lot of things in common with each other.”

Sonny Sharrock tried to play his guitar like John Coltrane. Were you trying to do the same with piano?

“No. What I found is a sound that matched his, as when I played the Wurlitzer organ with the synthesiser up on the top; you could pick his vibration out like anything. It was still not a saxophone, it was not a piano, but the vibration is like Coltrane’s sound . When I really noticed it, I guess, was on a piece called “Leo” from an album called Transfiguration. But if I play the same piece on the piano it’s not there, I don’t hear it there. Why would I ask, or expect, that the organ is gonna do what the piano does? They’re both different instruments.”

Are you feeling the presence of John when you’re playing that? Or are you trying to take it beyond?

“No, I still think there’s that unity, there’s still that sharing, and the light and the spirit of what he gave more than, ‘Oh lets take this a next step higher’. It’s me at a moment, its not me trying to further a legacy, I have no interest in doing that, it’s a landmark thing”

No, I was just wondering if you were trying to take that particular piece of music a stage further, advancing the legacy because you’re playing a totally different instrument?

“In my heart I don’t feel that. My feeling is that when I hear other people do it, I think that they’re re-creating. Creating someone else’s music to be invited into their own feelings, thoughts and design. That’s usually what I hear, a re-creation. You could be playing classical, say Beethoven, and its not taking anything away. It’s just not, well for one it’s not your music, it’s his music, which means you’re involved in a re-creation of what is already done. But we hear your effect, we hear your feeling, we hear your definition, and I never took it as that we were trying to improve on something. But I did hear one story, and I don’t want to mention his name, about a particular musician who played a very fine alto and was trying to improve on the music of a highly respected and celebrated musician. I thought that was so interesting because, to me, it just seemed like they were trying to perfect what was already happening there.”

“In my heart I don’t feel that. My feeling is that when I hear other people do it, I think that they’re re-creating. Creating someone else’s music to be invited into their own feelings, thoughts and design. That’s usually what I hear, a re-creation. You could be playing classical, say Beethoven, and its not taking anything away. It’s just not, well for one it’s not your music, it’s his music, which means you’re involved in a re-creation of what is already done. But we hear your effect, we hear your feeling, we hear your definition, and I never took it as that we were trying to improve on something. But I did hear one story, and I don’t want to mention his name, about a particular musician who played a very fine alto and was trying to improve on the music of a highly respected and celebrated musician. I thought that was so interesting because, to me, it just seemed like they were trying to perfect what was already happening there.”

Perfecting what was already perfect

Yes, but not improving. In other words, like TV. They did the remake but they didn’t improve it. They just made it better than what it was, because it had this aspect and this option and this application, sort of like the expanse of our internet. Who can say? Maybe the day will come when it’s so much better and so much improved. But I just saw them making themselves sound so much better, but not perfecting on what they already did.

When John and Pharoah Sanders deliver their pieces on the Olatunji record, you take them on unflaggingly.

“Well I think it was much easier for me because of my proximity to them and the fact that he believed so strong [in my playing]. When he asked me if I would like to join the band after McCoy [Tyner] had left I just said, ‘Are you sure? Is this what you want?’ and he said, ‘I’m positive’. Well I hesitated, I didn’t know whether to accept because I’m considering there are so many other people who’d be more qualified. But he said, ‘You know you can do it and I want you to’. Because of his assurance, his encouragement and his belief in me, I never felt half or less than anyone. I never felt like, Oh I’m going to have to come up to par and make myself favourable or acceptable because of him. His confidence in me was so strong. One day he said to me, ‘For you to come out from Detroit, this music is like a second nature to you, it’s just like it’s a part of you, a part of your life’.”

You’re released from that system then. what did that feel like?

“It felt like if you were to just walk out of this door and just see a new world, a new universe with so many opportunities in it. You know so many things to discover and so many vistas to look upon. It was so perfect for me. And I never felt locked in. I said what a freedom, and to have it without all of these boundaries and restrictions. Not that it was wild and undisciplined, because that was something we’d talk about. He said, ‘If my music ever became such that I’m playing without thought or without concentration, I’m finished.’ He said, ‘I’d never want to play’.”

I think free jazz is the most disciplined, you have to really listen to each other.

“To know where you are. Because even on the Transfiguration record, as I told you, it was like a communication going on with John’s spirit. You could hear it. You could hear the response and you could hear the reply, when it would come from the bass player or from [the drummer] Roy Haynes. That was good for me, because in performance you can’t be the observer and the one who’s outputting. But to listen to how everyone was so connected, so attuned and so responsive, THAT showed precisely what he was saying. You have to be disciplined, you have to be concentrated. You can’t just say, ‘Oh I’m playing for me and as I’ll do as I please’. Otherwise it would break down, like chaos.”

I like when you come in on with Rashied Ali and Jimmy Garrison like a little trio. Did you feel a bond? Separate for that instant?

“No I still feel we’re all there, because his [Coltrane’s] eyes are looking at me. He’s absorbing everything. When he’s playing we are all attuned his hands, his playing and what we have to do now as a trio. But when he’s not playing he’s not like, ‘Oh, I’ll be back in ten or fifteen minutes’, I mean he’s there. He’s still giving and feeling this activity, still pouring his spirit into the whole, the total [performance] instead of, ‘Oh, I can look away’. And so it’s all there.”

What about Japan?

“Oh, Japan was so special because the people were so lovely with such a deep admiration.

Americans were confused about this new direction.

“It wasn’t liked very well by Americans.”

But the Japanese embraced it.

“Oh they loved it. They liked everything we played. So when we saw that group of people who wanted to hear the older music, music that he’d do with Miles Davis… They wanted to live in the past and that’s something you couldn’t get John Coltrane to do. They’d say, ‘We want to hear Equinox’ or ‘We want to hear Mr PC’. He always played My Favourite Things’ and they liked that, that was one he would always play, but a lot of the other older pieces he wouldn’t play.”

Infinity?

“Some people didn’t like the addition of strings. They said, ‘We know that the original recording didn’t have any strings, so why didn’t you leave it as it was?’ And finally I made a reply because they don’t know what we were talking about, about music or architecture or biology, you name it. They don’t know when or where… They don’t know what happened or transpired between myself and John. So when they would give an opinion I just replied, ‘Were you there? Did you hear his commentary and what he had to say? Are you aware of it?’ So it just became something that I consider didn’t require an answer.”

It was a very personal statement.

“We had a conversation about that piece and about every detail. We had a long talk about it and we were talking about the dimension of things, and he was showing me how the piece could even include other sounds, blends, tonalities and other resonances such as strings. So that’s how it happened, and I’ll tell you it teaches living space, and we had a very lengthy and wonderful talk about it. He talked about cosmic sounds, higher dimensions, astral levels and other worlds and realms of music and sound that I could feel.”

Cosmic Music came out on Coltrane Records and John did the cover drawing.

“Yes it did. Those were his markings.”

Coltrane Records?

“I thought it would be nice because he, I would say, on a regular basis would speak about taking some control over your own destiny in terms of recording. In terms of the management of the recording that you’re involved. He was saying that a lot of musicians do not want to be bothered. They don’t want to handle statements, they don’t want to be concerned about audits, they don’t want to be concerned about payments that go out to others, you know, all of the whole buying/selling process. They just want to do their music and get paid. He said, ‘But I really think that young people should think twice about how they want to regard their musical career and their musical involvement. I think they should take more control over it’. And that’s why it came out. Because he said, ‘If you can go over to someone else’s studio to record and give it to that company over there, your tape, do it yourself!’

But only Cosmic Music came out like that.

“What happened is that Impulse! came to me and said, ‘We understand the situation that John gave you these recordings, because these were the recordings that he made when he was creating work for musicians, and we understand how it evolved. The only thing is that, technically, he’s still under contract, so basically that makes us own the material’. And they were very courteous, they were not in any way forceful or unkind, they simply said, ‘Why don’t you let us do it. We can take this album you’ve done, put our Impulse! stamp on it and let’s start from there, and [you can] go on making music and playing’, so it was fine. So for that short time I think I learned something. I was not inspired to have a record company, but it was a good experience.”

Did they offer you a contract as a solo artist? How did you become a solo artist?

“Uh huh. It was John. It was through him and Bob Thiele, because they started talking about it. One day John came home and he said, ‘What do you think about making an album?’. I said, ‘Yes, it sounds like it would be nice’, and the next thing you know I’m speaking with Bob Thiele. He said to me, ‘I’ve been talking with John and we think maybe you might want to do your first album with us’. I said, I really like that idea.”

The Monastic Trio. How many takes in the studio?

“Usually it wasn’t one take because you usually didn’t have your sound right. In those days everybody recorded in the open, we hardly ever used baffles – those sort of bumpers – because the musicians wanted to see each other for the continuity.”

Did the recording process get in the way of the music creatively

“No, I just know that it isn’t like you’re performing. And it isn’t like when you sit alone and practice, it’s different. Its all different, its different moods, different atmosphere and different feelings.”

Playing the harp.

“I like the sound of it. I would spend a lot of time with the instrument, and I also wanted to bring the harp out for John. It was his idea and what he wanted. In fact, one evening he was playing at the Village Vanguard and we took the harp, so that was kind of fun.”

Did he like the harp?

“He said, ‘I like the sound of it’. If at home and it was by an open window, the breeze coming in would cause the strings to sound and he could hear the wind playing through the strings. He liked it! The harp has to be played with the fingers plucking the strings, but it uses air and that’s what I liked so much about it.”

So a harp and a saxophone aren’t that far apart.

“No. I think it’s even closer, because with a piano the notes meet with a mallet inside and that meets with a string but it doesn’t breathe. It’s such a wonderful instrument. With the harp, maybe that’s why we think of heavenly things and divine things, because we get that rush of the wind.”

I feel there is a certain amount of air in a piano.

“I think a musician creates that atmosphere, that it is breathing and alive. I think it comes from the person. Because you can play notes and give them shape and a definition far beyond even, maybe, what the inventor [of the piano] thought up. We could hear notes that would reflect; notes with intellect; notes that would contact their sympathetic note. I know I have myself intuitively felt it vibrating, like electricity coming through.”

You’ve always been associated with the harp.

“I just never considered myself to be a harpist to begin with and I didn’t have a lot of background experience [with the instrument] either. But people would say, ‘Oh, she plays harp’. They would almost go to the harp first, and then the piano. In earlier years I would have them rent me a harp. I remember once I rented a harp from a place and it was very hard to keep it tuned. And these youngsters who were out of college were at the gig and they were saying, ‘We were waiting, we wanted to hear the harp, we want to hear the harp!’. So I said, ‘This harp is not up to par this evening’, but they said, ‘We don’t care! We just want to hear anything, one note!’. So I said, ‘OK, fine’, so I played and they were just delighted. Delighted.”

I see what they mean. It’s such a lovely thing to hear.

“There was another person from the city of Detroit [who played the harp] and her name is Dorothy Ashby. She was a most beautiful harpist, the very best. She used her voice with the harp so beautifully. She wasn’t much older than me, I think four years maybe, and she seemed to be getting a lot of fame before she got ill.”

You collaborated with The Rascals on Peaceful World. song called Little Dove.

“I think it was because of the harp I got involved with Felix Cavaliere and also Laura Nyro. She said, ‘Oh you have to play on my album. It’s just like you can feel the waves and hear the music just reverberating and pulsating’.”

So was it Laura or Felix who asked you?

“Oh that was for Laura’s album [Christmas And The Beads Of Sweat].”

And Felix asked you for the Rascals?

“Yes.”

How did it feel being in the pop world

“I didn’t feel anything because we were all disciples of Swami Satchidananda. Myself, Laura, Felix and Peter Max. That was the connection.”

How did you meet him?

“I was introduced to him by a friend of mine from Detroit that I had not seen in years. His name is Bill Wood, he played bass and Swami Satchidananda was his guru. I had forgotten why I was in New York, but I saw him and asked him, ‘What are you doing with your life? Why haven’t I seen you?’. And he said ‘I’m doing fine. I’m living here now’, and I said, ‘Well what else are you doing? What are you studying?’. And he said, ‘Well I have a guru’. I said, ‘You do, you’re serious? Well tell me something of him’. So he gave me some description and I said, ‘Well, I would like to hear him speak’. So he invited me down to church and that’s when I saw and heard him, I thought it was excellent. Because he had a number of young people down there who thought he was a very interesting person. They felt like he had become like a father to them and that they felt included. They felt like a family and he had got a lot of them away from drugs that steal their sweet life.”

He addressed the Woodstock festival in ’69

“Yes, they got him out there. I wasn’t there. I met him right after Woodstock, maybe ’70. They called and said that they were so fearful that those young people were going to tear the place apart that he’d have to come out and do something. So he went and talked to them of peace, and he said there was not one incident in the whole three days. So that was very good news, they needed that.”

What did you learn through him?

“Well some of the outstanding things that I learned was that in life we make appointments. And when we make an appointment there’s desire connected with it, and that desires create the possibility of disappointment, frustration and all kinds of negative responses when they’re not fulfilled. So he says, ‘Go back to the root of the whole situation, don’t attach yourself to an idea so strong that you make an appointment, because if you make an appointment you can get ready to be disappointed. But say, if you want to build a ship, build it in a detached manner. Don’t build it subjectively, don’t build it by putting your full faith into a technical, temporary, mundane, or materialistic thing. Go about it in a detached way. Detached doesn’t mean disliked, it just means that I don’t want this project to consume me. It will if I allow it. If I subject myself it ends up binding and controlling me. I can’t sleep at night because that’s all I’m concerned about. So I will go and do my work objectively.’ That’s one of the best lessons I’ve learned that he taught us.

What do you mean by Universal Consciousness?

“To not always attach ourselves to everything because we live in a world that’s so changing. If it’s true what can we do? We’re helpless to act against change, but we shouldn’t invest so heavily in our material world, our mundane existence. We won’t be here anyway after 50, 25, or maybe even next year. We’re going on to a higher dimension, another whole realm of existence. But many people have just hurt themselves. An important part of your being is your thinking, your mentality. It shows you that life exists in all forms, in all ways and God didn’t intend for man’s existence to be temporary. That’s why I believe that we’ve got spirituality. Religion divides people. Religion creates problems when there’s not an understanding that we should accept all of our fellow man. Whatever your faith in God is, let’s not be critical, let’s not be judgmental, but most religions are so sectarian, so orthodox, and so much into believing that their God is the only one it makes problems unnecessarily. Spiritually we don’t have to concern ourselves with tenets and precepts and concepts, and that this faith is based on that statute, this code and that principle”

So it’s not your own God, it’s everybody’s God

“Yes. And if we would put in one fourth of the time into trying to understand our spirituality that we put into wanting to grow more wealthy, I think we would find some of the incredible things that are occurring in our universe that we need to be aware of. We’d be more at peace with ourselves, we’d have less thoughts and petty concerns about who’s better and who’s trying to be better.”

So what is the role of a guru?

“According to the technical meaning, he’s the one who removes the nations. He removes discrepancies, he removes doubt, he removes disbelief. He’s the one that’s clearing the area, purifying in your life, removing things that have stood as obstacles and impediments in the way. He cannot do your work.”

Is he the voice of God?

“Yes. When he is avowed to that knowledge, then you can trust him to give God’s message and not his. We’re all at different phases and stages of our evolution. Some of them are away past all of us and some are at an elementary level, it’s just when you know that’s God’s message. But how do you really know when you don’t have a confirmation? That means you must do your part as well, so if anyone will tell you something you just ask yourself, ‘What happened? Because I was at my meditation this morning’.”

How did you part from Swami Satchidananda?

It’s not [a] part[ing], oh no! I want to go and see him in the year 2002, I want to go and see him soon. Mine was locale, leaving New York, moving to Los Angeles. It’s just a technicality, just moving, so I don’t have the association. I sort of rarely see him unless he’s coming out here for a program for him in Santa Barbara or down town. I go there. I go to see him. So we spend time, we talk and I’ve been out to his place in Virginia. There’s like a thousand acres of his beautiful complex with a beautiful LOTUS [Light Of Truth Universal Shrine] temple of ALL religions; native American, Hinduism, Christianity, Islam, every faith is represented.”

And you have your own centre? What do you do there?

“Yes, I have my own centre right here. On Saturdays I go and have class for the young students from the ages of 15 up to about 30 Then there are initiate students who took a mantra. They recite their mantra, they recite their raga, study, meditate, do karma yoga, do sophomore service in the community, or wherever, and meditate and pray. That’s their instruction. And they’re going to grow up based on their effort, not on what somebody else did, it’s going to be up to them. So that’s what happens there and the ashram is just the sort of place that’s more conducive for it, where we’ve got forty acres so you can go sit by the stream, and you can read… A number of them are young people who are working and their children go to regular school; we don’t have a commune type of a place. And now all those children are growing up and they’re going to UCLA and various schools all over. One is in New York, studying music. On Sunday afternoon I give a talk that’s for the senior students and the public are invited.”

Did Swami Satchidananda’s teachings play a part in your music?

“Yes, he loved music and he would chant. Well you know he was on that one take; “A Love Supreme”! Yeah, he gave it as talk, because he really let A Love Supreme reign throughout the year. His voice was so beautiful on that tune.”

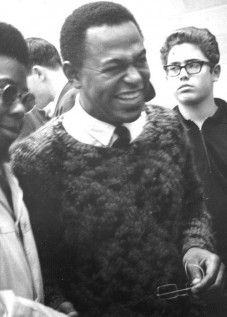

Alice Coltrane at Hill Auditorium, Ann Arbor, on what would be John Coltrane’s 80th birthday, Sept. 23rd, 2006

Lord Of Lords?

“That record was so special to me because practically every aspect of it is like a meditation, and the [cover] photograph was so unlike any one ever taken. It was the expression, it was what appeared to be the underlying substance of some higher energy vibration. When I looked at it I could see it was more like identifying with the soul than it was with the external person’s features or anything like that. And then the music became a meditation where each selection told its own story. Although it’s one that you can write down, I sometimes think things are better left in that realm of mystery or the unknown.”

Illuminations with Carlos Santana?

“He [Santana] was so happy, so buoyant, such a beautiful soul and everything was wonderful. Everything was like a new and wonderful, joyful experience. And he brought that youthful dynamic into everything that we did.”

You played alongside Joe Henderson on his The Elements album?

“My remembrance is he just asked me if I would record with him, but I believe that also some of the A∓R people had asked him if I would be available to appear on the album, so he called me. But I’d known Joe for years from Detroit.”

Encouraging free jazz players.

“I think more open, because we weren’t really playing in freeform as much, but I think these musicians were capable of playing in that way and they were also open to it. Because some people didn’t want to play like that. They weren’t interested and they made it very clear, ‘No, I don’t like it. I don’t like progressive jazz. I don’t like this avant garde music.”

Your years at Warners?

“Through Ed Michel who was working for them, because we had been working all those years together at ABC. He’s a fine person. I have never heard him question anything that I ever brought to a session. I never heard him complain, I never heard him say, ‘I don’t think they’re going to like this’. He’s never said anything at all, whatever was there he seemed very pleased with it.”

Transfiguration?

“That was just a special evening. Even the people, all the elements, everything was in place somehow. The music, the musicians, just the atmosphere. It was so interesting because, to me, even at some levels it was higher than a concert audience. It was like a gathering of people who give something that we also receive. And we also give to their receptivity, what they’re there for. So it was like that sharing, that giving, that just kept reverberating and encompassing the whole evening. That’s when I started to see that audiences do become a part of the music in their own way. I think you become aware of where their heart and their spirit is, because it’s coming towards you. What you’re doing is just like as if that’s what they’re doing. They’re breathing it with you, they’re living it through with you, they’re receiving what you experience or perceive, but also they give. They give inspiration, and then you find out you’re not just playing a solo, you’re not playing for yourself, it’s for everybody. When we talked earlier about John’s idea; it’s for all people for all the time, for the universe itself, for God. It wasn’t just for the 500 people present in that auditorium. Some of them will have something like a spiritual experience, sometimes people put themselves very deeply into sound. So deep into it that they give up everything. It’s like they renounce everything at that moment just to live those moments of music, and that I’ve seen several times.”

Source: Alice Coltrane: Enduring Love, Wire, June, 2004

Tags: Alice Coltrane, Jazz, Spirituality