The Wild One: The True Story of Iggy Pop -a review by John Sinclair

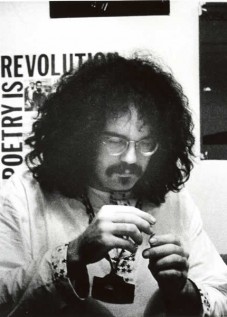

Iggy Pop, 1968 by Emil Bacilla

The Wild One: The True Story of Iggy Pop

Per Nilsen & Dorothy Sherman

Omnibus Books

By John Sinclair

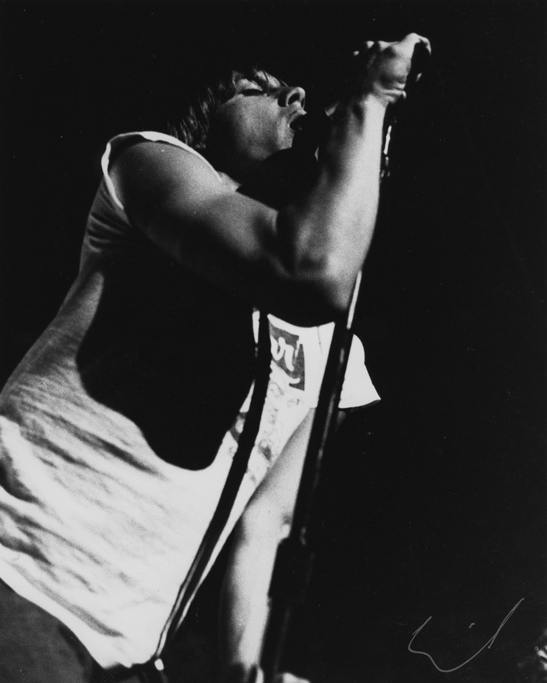

Ann Arbor’s own Iggy Pop, the shamanistic pioneer of post-modern pop music who can reasonably be dubbed the father” of “punk rock” by virtue of his slash-and-burn, search-and-destroy theatrics and thunderous, aggressively minimalist musical attack as leader of The Stooges (1967-74), has cut a uniquely compelling figure in the pantheon of rock legends and demi-gods for more than 20 years now.

Although the Ypsilanti-born Jim Osterberg–he got the “Iggy” as the drummer in a teen band called the Iguanas, and his colleagues in The Stooges added the “Pop”–has never enjoyed a hit record of his own nor the concomitant mass audience generated by regular radio airplay, his career has sustained an ever-growing cult following that remains fascinated by the Ig’s impassioned commitment to his own twisted aesthetic and his violent disdain for commarcial success.

Iggy’s early recordings with The Stooges–their eponymous debut album on Elektra (1969), Fun House (1970), Raw Power.(1973), Metallic KO (Live at the Michigan Palace, Detroit, February 1974)–bristle and pound with an energy and a point of view previously unknown in pop music.

Not a “rock & roll band” in any existing sense of the term except for their instrumentation and attitude–as Iggy told Anne Wehrer, “We couldn’t possibly play our way through a Chuck Berry tune”–The Stooges were assembled by a 20-year-old Jimmy Osterberg to “try to do something as different as possible from anything going on at the time.”

While the Ig had developed a local reputation as a rocker and then, with the Prime Movers, an accomplished blues drummer, he decided to pursue an innovative, defiantly iconoclastic musical direction after spending eight months in Chicago playing with blues bands–J.B. Hutto, Big Walter Horton, Johnny Young–in all the south-side joints and crashing in Bob Koester’s basement at the Jazz Record Mart.

When he peeped the reality of the blues idiom–that it was a form developed by African-American musicians to express with great accuracy the everyday content of their lives–he reached a startling conclusion:

“When I found that out, I knew I had to come home and make my own music…. I’ve got to take what I’ve learned here and apply it to my own experience….. I wanted to make songs about how we were living in the Midwest. What was this life about? Basically, it was no fun and nothing to do. So I wrote about that.”

Bypassing completely the sizable pool of competent, locally established rock & roll musicians, Iggy selected a pair of aspiring but basically unskilled brothers–Ron and Scott Asheton, from the west side of Ann Arbor–and proceeded to communicate his concept to them through months of doing “nothing but talk bullshit” and then several more months of rehearsing the kind of music Iggy’d been trying to tell them about.

He literally taught Scott Asheton the fundamentals of drumming and even designed a bizarre drum set for him out of a pair of 55-gallon oil drums “which I got from a junkyard.” Ron Asheton dealt with the huge droning bass sound Iggy was looking to hear, and the Ig featured himself on Farfisa organ, electric piano, or either “this sort of wild Hawaiian guitar with a pickup that I invented, which meant that I made two sounds at one time, like an airplane.”

This early Stooge configuration stood up in practice until the night Iggy saw the Doors play the U-M Homecoming dance at Yost Field House in late 1966, where, as Per Nilsen puts it, “Jim Morrison had proved to Iggy that you could do virtually anything on the stage and get away with it. Iggy saw a completely loaded Jim Morrison roll around the stage and do gorilla imitations.”

Osterberg says it right out to Dorothy Sherman: “It was after I saw Jim Morrison that I decided I’d be a singer, no matter how much I laughed, cried or died. But what he meant by “singer” was something very different from any role models extant–Iggy acted out the imagery embodied in weird little tunes like “I’m Sick” and “Asthma Attack,” improvising wildly with sounds and incredible movements in front of “this thunderous, racey music, which would drone on and on, varying the themes…like jazz gone wild. It was very North African, a very tribal sound: very electronic.”

The band was first called the Psychedelic Stooges and, as Iggy told Dorothy Sherman, the name was “a sort of tribute” to the Three Stooges: “We loved the one-for-all/all-for-one of the Three Stooges, and the violence in their image. We loved violence as a comedy. Besides sounding right, ‘stooge’ also had different levels of meaning: is calling yourself a ‘stooge’ a self-insult?”

The Stooges revealed their mind-blowing version of contemporary music on Halloween night 1967 to an invited group of friends at the Ann Arbor home of their first manager, Ron Richardson. Four months later, on March 3, 1968, the Psychedelic Stooges made their public debut opening for Blood, Sweat & Tears (!) on a Sunday night at the Grande Ballroom in Detroit.

The Stooges actually got the gig when BS & T, coming to Detroit on their first national tour, nixed the MC-5 as its opening act but accepted the totally unknown Psychedelic Stooges, who totally destroyed the “completely amazed” crowd with their raw, throbbing, primitive electronic wall of sound and the spectre of Iggy Osterberg dancing disjointedly out in front of the band, his face painted white and his menacing, eerily intoned vocal chants alternating with instrumental breaks on theremin, amplified vacuum cleaner, and his home-made Hawaiian guitar.

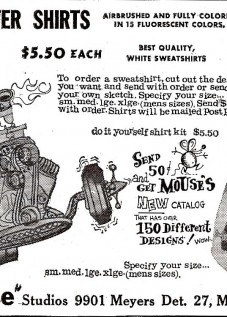

“People just didn’t know what to think about us,” Ron Asheton recalled for Dorothy Sherman. “We had our own instruments. For example, we poured water in a blender and put a mike on top of it. We got this really weird bubbling water sound which we put through the P.A. And Iggy danced on a washboard with his golf shoes!”

The Psychedelic Stooges played several carefully-selected dates in Detroit, Ann Arbor and outstate Michigan over the next six months, often on bills with the MC-5, and never failed to shock and astound unsuspecting audiences who had come to see a “rock & roll band” and ended up witnessing an indelibly unique and strangely moving performance experience which was almost completely different every time out.

By the end of September 1968 the Stooges had been signed by Danny Fields to a major recording contract with Elektra Records, in tandem with their pals the MC-5, and soon unleashed their blasphemous sound and fury on the world at large.

The rest, as they say, is history, and you’ll find the whole strange story recounted calmly, date by date and performance by performance, in Per Nilsen and Dorthy Sherman’s excellent new biography, The Wild One: The True Story of Iggy Pop. Dorothy, a Detroit native, conducted the thorough, well-pointed interviews, and Nilsen wrote the text, designed the book and typeset the generously illustrated package for publication in England last year.

An American edition with a new cover and even more photographs was issued at the end of the year, making this impressively researched, clearly written report available to the Ig’s many fanatical followers here in the States. If you’re one of them, check out The Wild One for yourself. Like its illustrious subject, it’s definitely the real thing!

–Detroit

1989

(c) 1989, 2006 John Sinclair

All Rights Reserved. reprinted in It’s All Good: A John Sinclair Reader, Headpress, and Johnsinclair.us

Tags: Iggy Pop, Reviews, Rock 'n roll, Stooges