The Free University of Detroit

THE FREE UNUIVERSITY OF DETROIT

He who knows others is learned, he who knows himself is wise.

— Lao Tzu

Free University origins can be traced to seventeenth century old-world religious communes, the brotherhood of Freemasons, and secret societies of the French revolution. Free slave schools appeared in the rural American south in the mid-1700s set up by the ‘Society to Propagate the Gospels’, to enable slaves to read the bible. Dangerous illegal underground slave schools educated people in bondage and worked in tandem with the Underground Railroad, to achieve their freedom.

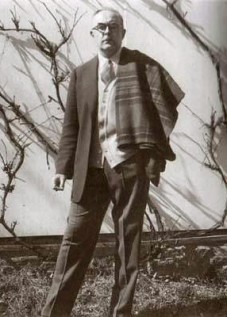

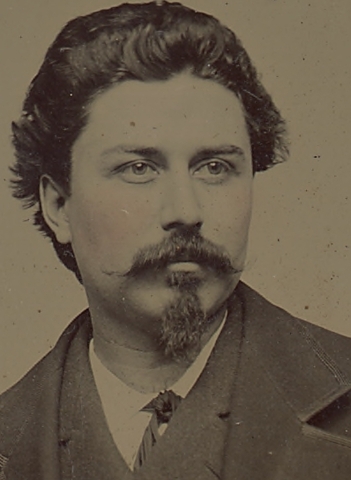

Charles Joseph Antoine Labadie (April 18, 1850 – October 7, 1933) Anarchist, printer, collector of radical literature and ephemera, as a young man in Detroit.

Anarchist schools of the late nineteenth century were hinged to labor movements and social idealists. Joseph Labadie, a well-loved Detroit anarchist, printer and labor movement leader was born in Paw Paw, Michigan in 1850. A printer by trade, he came to Detroit in 1872 and organized the first cell of the ‘Knights of Labor’ in Michigan. Begun as an organization to rally and support labor workers, the ‘Knights of Labor’ was a fraternal order founded in 1869. Committed to uniting labor workers, it was the first to include women, the unskilled and African-Americans. It became North America’s largest labor organization of the nineteenth century, claiming over one million members. Secret handshakes and ceremonial rituals were important elements of the order.[i] Labadie despised the secrecy and occult trappings helping to end them. He defined anarchy as “a synonym for liberty, freedom, independence, free play, self-government, non-interference, mind your own business and let your neighbor’s alone, laissez faire, ungoverned, autonomy, and so on… The doctrine of personal freedom is an American doctrine, in so far as the attempt to put it into practice is concerned, as Paine, Franklin, Jefferson and others understood it quite well. Even the Puritans had a faint idea of it, as they came here to exercise the right of private judgment in religious matters. The right to exercise private judgment in religion is Anarchy in religion.”[ii]

Joseph Labadie was known for publishing his own small radical magazines including the influential ‘Advance and Labor Leaf,’ his column ‘Cranky Notions’ was a public favorite that appeared for years in radical presses into the 1930s. Labadie collected important letters, manuscripts and anarchists publications beginning in the 1870s. In 1911, he donated the Joseph A. Labadie collection; “one of the oldest collections of radical 19th century history in the United States” and resides as part of the rare book collection at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. It has grown to encompass the writings of twentieth century and current radicalism and has inspired other collections in the United States and beyond, today its “the most widely used of all of the library’s special collections.”

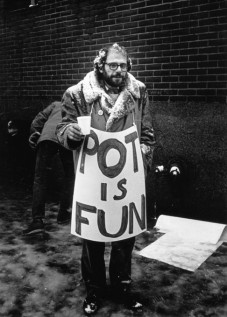

The Free School Movement of the 1960s was an extension of the 19th century Anarchist Schools and early labor movements, as well as the artistic avant-gardes from the 1850s through the 1920s. The idea of the Free University of Detroit (FUD) was born almost simultaneously with the founding of the Artists Workshop in 1964, but wouldn’t begin its operation until 1966. Inspiration for FUD came from a combination of teaching models; The Free University of New York, the teachings of Ezra Pound, Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Black Mountain College, Allen Ginsberg, New Music Society and Monteith College. The Free University came during the flowering era of new poetry, that also valued world experience and living-in-the-now, as opposed to corporate systems, professional teaching certificates, advanced degrees and traditional learning techniques. James Semark remembers the FUD idea as naturally growing out from the publicly free poetry and jazz workshops held at the Workshop space since 1964.

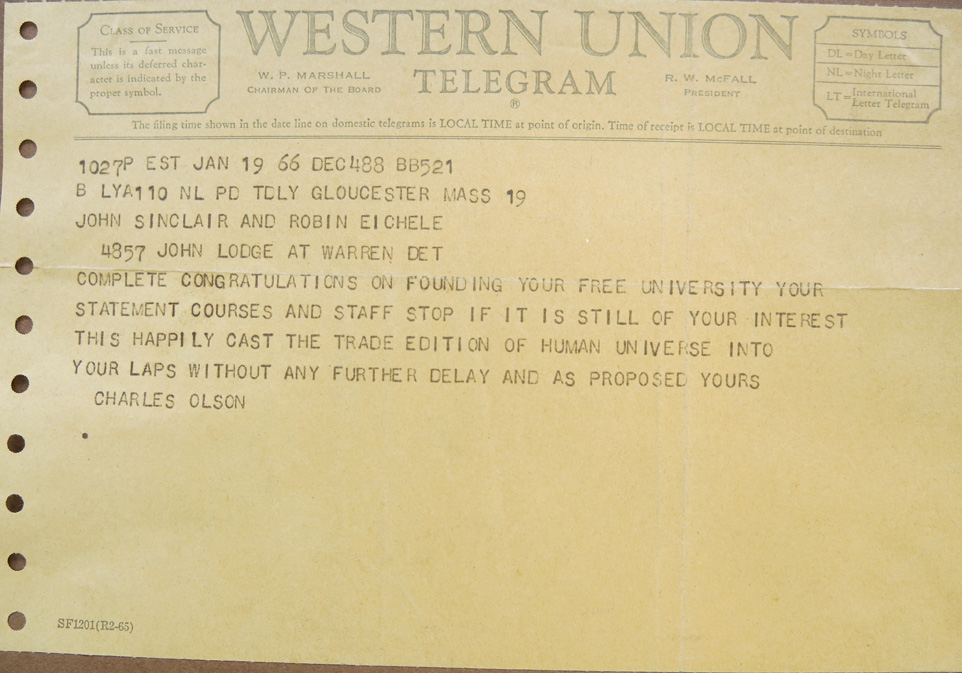

Charles Olson was a major influence and supporter on the formation of the FUD, and pleased with efforts going on in Detroit. To lend support he offered the Workshop the publication of Human Universe, and sent on January 19th, 1966, the following telegram:

“COMPLETE CONGRADULATIONS ON FOUNDING YOUR FREE UNIVERSITY YOUR STATEMENT COURSES AND STAFF STOP IF IT IS STILL OF YOUR INTEREST THIS HAPPILY CAST THE TRADE EDITION OF HUMAN UNIVERSE INTO YOUR LAPS WITHOUT ANY FURTHER DELAY AND AS PROPOSED YOURS CHARLES OLSON.”[iii]

“COMPLETE CONGRADULATIONS ON FOUNDING YOUR FREE UNIVERSITY YOUR STATEMENT COURSES AND STAFF STOP IF IT IS STILL OF YOUR INTEREST THIS HAPPILY CAST THE TRADE EDITION OF HUMAN UNIVERSE INTO YOUR LAPS WITHOUT ANY FURTHER DELAY AND AS PROPOSED YOURS CHARLES OLSON.”[iii]

At the Workshop, Olson was himself was “an example of a life-force that we can use as guides or standards in building our own lives, just as they built theirs, to be of use to all human beings on this earth… [Quoting Olson in Human Universe]: The proposition is a simple one… energy is larger than man, but therefore, if he taps it as it is in himself, his uses of himself are EXTENSIBLE in human directions and degree not recently granted.”[iv] Sinclair correctly saw Olson and his Human Universe, as creating a “bridge for those who followed—Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Sun Ra, LeRoi Jones, Allen Ginsberg, and now all those men who are my own contemporaries. Albert Ayler, Pharoah Sanders, Marion Brown, Roswell Rudd, Frank Smith, Burton Greene, Charles Moore, Lyman Woodard, Stanly Cowell, Ron Caplan, George Tysh, James Semark, Robin Eichele, and the many others who are to follow just because the gate has been opened and the center is there for all who can see it to see. These are pure men. Men who made use of themselves because that is what they have to work with and for no other reason. What they are working with is their selves and that is precisely what they are getting down. Their Work, (art) is what they are. Olson say’s it: Who can extricate language from action? They are the same thing.”[v] The connection between Olson and the Workshop was being developed and solidified by their ties to a trade publication of his important collection of essays, Human Universe, which Robin Eichele was about to print on the Workshop press. Complications diverted the publication, which went on to be published by Grove press.

FREE UNIVERISTY DETROIT CURRICULUM

FREE UNIVERISTY DETROIT CURRICULUM

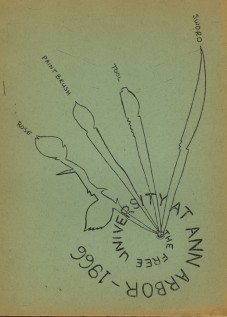

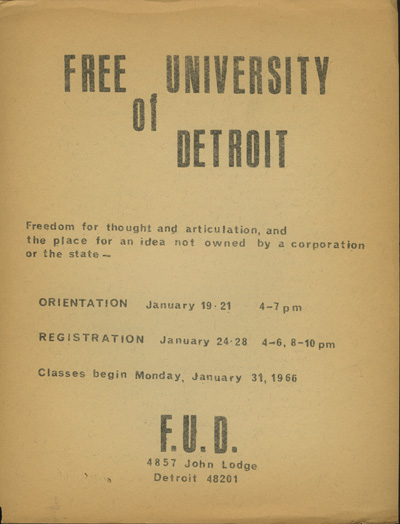

Flyers were made and passed out around Wayne State University and Monteith College to generate interest. They announced: FREE UNIVERSITY OF DETROIT, “Freedom for thought and articulation, and the place for an idea not owned by a corporation or the state—ORIENTATION: January 19-21 4-7 pm, REGISTRATION: January 24-28 4-6, 8-10 pm, Classes begin Monday, January 31, 1966. The address for the F.U.D. was 4857 John Lodge, home of the Artists’ Workshop.

The class schedule for the Winter-Spring 1966 term:

Mondays 7:00 PM: Media & Non-Rational Communication (Henry Malone)

9:00 PM: Community Organization/ New Left (Barry Kalish)

Tuesdays 7:00 PM: Poetry Seminar (John Sinclair & Robin Eichele)

9:00 PM: Creative mathematics (Arnold Skulsky)

Wednesdays 7:00 PM Philosophy & Music (Lyman Woodard)

9:00 PM: Contemporary Jazz & Jazz Criticism ( John Sinclair & Charles Moore)

Thursdays 7:00 PM: Modern Colonial Revolutions (Jan Garrett)

8:30 PM: Self-Realization Study Group (Jim Semark & John Collins)

9:00 PM: Contemporary American Prose & Drama (Sinclair)

Fridays 7:00 PM: Life Drawing (Howard Weingarden)

9:00 PM: Acting/Theater Techniques (Hurst Rinehart)

Saturdays 1:00 PM: Photography (Magdalene Arndt Sinclair)

3:00 PM: Ensemble Music Workshop (Charles Moore)

Sundays 7:00 PM: Free concerts of the New music plus readings by Detroit Poets

Other class times are arranged; interested students may contact the professors for time and place:

The Surrealist Stance (Allen Van Newkirk, 4825 Lodge)

Music Theory & Music Composition (Jim Semark, 4821 Lodge)

Dialectical Sociology (James Winegar – starts March 15)

Seminar in Pre-Homeric Greek Civilization (Sinclair, Eichele, Van Newkirk)[vi]

The Free University of Detroit represented a major departure and alternative to higher educational offerings. From the FUD catalog and opening statement:

“A Free University here in Detroit represents for us the second major step toward the construction of a permanent community of committed artists and scholars in this area—the first step being the formation of the Artists Workshop Society in November 1964, the organization of the FREE UNIVERSITY is an organic and necessary outgrowth. The FREE UNIVERSITY here will attempt to fill in some of the many gaps that exist in the established educational institutions in this city and elsewhere. We hope for one thing to find a way (or ways) back to the original sense of the word “professor”—the FREE UNIVERSITY’s faculty comprises active artists and other workers who are deeply committed to their work and to the work of sharing what information they may have which can help other people to more human life possibility than they are offered elsewhere in our society. These workers then will be professing just what it is they have come to know or understand. Prevalent dualistic (“objective”) educational methods will be largely jettisoned, and a positive monastic mode of engagement will be the primary term of our involvement with the FREE UNIVERSITY’s students.

Enrollment in the FREE UNIVERSITY of Detroit is open to any student who has a genuine interest in learning and an equal need to expand his own consciousness through organized study. The student here will be expected to involve himself in his studies for their (his) own sake,i.e., without any promise or demand of degrees, credits, and other token rewards – which have come to mean, finally, only meal tickets on the great American soup line. The work is always its own reward, no matter what other (alien) value may accrue to it. FREE UNIVERSITY students will be subject only to their professors’ requirements and to their own emotional and intellectual discipline.

The FREE UNIVERSITY here will serve them then, hopefully, as a new kind of graduate school for those who have found their standard formal education less meaningful and useful then they had anticipated; as a supplementary educational means for those students now enrolled in school elsewhere who likewise find something vital lacking there; and as an intensive training agency for those younger people who may have not yet been in college but who need to move toward a broader educational experience. Again, hopefully it will provide a foundation for a strong healthy university that will grow organically, in quantity and in quality, with both its students and its faculty.

We would like to thank the FREE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK and also Charles Olson and Robert Creeley, formerly of the Black Mountain College faculty, for their help and encouragement.”[vii]

Opened on January 31st, 1966, its emphasis was on the contemporary arts, an area not being strongly represented in the present University curriculum. Classes were held in a loosely structured lecture-discussion format. John Sinclair was quoted in The Collegiate, “The objective of the present University student is to get a degree – then you can get a job and then you can go to the Fisher Theater… You go to class because you have to… In some of these classes the only reason you go is to get a degree. In FUD if someone doesn’t want to do the work, they don’t come. The people in the class are directly interested.”[viii] The FUD had 18 classes scheduled for their winter-spring term, and 15 professors. Tuition fees were $10—a semester, that represented “a minimum commitment on the part of the student.”

Allen Van Newkirk said the purpose of the FUD was “not only to offer information, but (the Free University) was an alternative to a whole way of life… to get men and women away from careerism… The University has become a method of feeding corporations (including universities) with recruits. In the undergraduate level knowledge is obtained in an impersonal manner, and the graduate sections have become super-specialized areas to provide consultants for universities and corporations… Whole areas of knowledge have been completely ignored, the Free University will help to revitalize the University itself.”[ix] Leni Sinclair stated that the present “methods of teaching (in the University) are getting poorer as more and more students come in. Classes are getting bigger and the talent gets lost in the big mass.”[x] FUD was a utopian anarchist action, planted in the middle of an under-responsive educational system; a system geared for producing chemists, mathematicians, engineers and scientists.

The Detroit Free Press covered the FUD as a caricature; emphasizing the squalor, dirty front windows, cigarette smoke and rudimentary classrooms under the headline, ‘New School’s Creed: Think As You Like’ and the byline “the cheapest college in town does business in an abandoned store with no blackboard in sight… To dig the Free University of Detroit, you have to sit in the circle around a ripped hassock that rests on the worn floor of an abandoned store at 4857 John Lodge. To be with it, you have to see that what passes between these students (are) unfettered thoughts about poetry written by poets that nobody except themselves and a very few others have ever heard about.. the opportunity to study poets like Robert Creeley, Allen Ginsberg, LeRoi Jones, and Gary Snyder; to talk about “The American Street Scene from Mezzrow to Malcolm X” and modern revolutionaries like Che Guevara and Mao TseTung… Like the philosophy and music class the poetry seminar was neither planned nor programmed. It had some of the qualities of the orthodox seminar, with overtones of the séance and the late night bull session when people have just about run out of things to say”[xi]

The Free University was not destined for long life. Divisions within the workshop, negative press, personal changes and developments from the outside led to a tighter new structure within the Workshop, which was expressed as Trans-Love Energies. In 1966, the Grande Ballroom had already opened and rock n’ roll energy was quickly replacing jazz and beat poetry as cultural messenger. In late 1966, Robin Eichele left to study film in London. Allan van Newkirk took his journal Guerrilla to New York. The front cover of Work #4, proclaimed LOVE+ENERGY=WORK4in liquid psychedelic type, and an acid inspired design by Gary Grimshaw, an artist who would be a central voice in the new Workshop order. Inside quotes of Work #4 by Olson and Coltrane were now joined by the Jefferson Airplane: Hey people now, smile on your brother. Let me see you get together & love one another right now. Work 4 was a massively thick issue: 150 pages of dense mimeographed pages, a three month issue: summer/fall/winter/ 1966 or “3-in1 without the oil”—the issue included the anti-imperialist rant/poem ‘Poisoned Wheat’ by Michael McClure which shouted out:

I AM NOT RESPONSIBLE FOR THE TRAITOROUS

FASCISM AND TOTALITARIANISM THAT SURROUNDS me!!!

…I AM NOT RESPONSIBLE

FOR THOSE WHO HAVE CREATED

AND/OR CAPTURED the CONTROL DEVICES

OF THE SOCIETY THAT SURROUNDS ME!

….CAPITALISM IS FAILURE!

It creates overpopulation, slavery,

and starvation.

…Society is masochistic.

It deludes itself that a status quo is

Maintained. It is driving for its destruction.

WESTERN SOCIETY HAS ALREADY DESTROYED ITSELF![xii]

The Free University of Detroit dissolved and became part of the street culture—a world-wide culture, coming out in large numbers as a mass movement of disaffected youth. The Workshop efforts were part of a growing super-movement, fighting for an end to the Vietnam war, and holding to its pursuits of creativity and freedom. Values in society were changed and dismantled. The pursuit of happiness and self-realization joined the new music taking the stage.

* * *

MONTEITH COLLEGE ORGANIZING PRINCIPLES

Major innovations in educational curriculums were made after World War One. International free university movements grew out of European avant-garde’s in Munich, Berlin, Prague and the Ukraine. The University Without Walls (UWW) movement in the United States was born out of the experimental colleges of the 1920s and 1930s; colleges like Antioch, Bard, Black Mountain, and Sarah Lawrence, where each committed themselves to developing an undergraduate program that focused on the personal growth and development of the individual. A curriculum of fine arts, independent study, and experiential learning was emphasized. In 1964, a consortium of ten colleges gathered together to discuss and explore their collected concerns. Known as the Union for Research and Experimentation in Higher Education (UREHE), the 10 member group which included Monteith College of Wayne State University, developed eight organizing principles:

1. Inclusion of a broad range of persons, as many beyond the usual age for college would like to have and would profit from a college education. Many of them have acquired much skill and knowledge from their life experiences, which can and should be recognized as contributing to college level work and the degree.

2. Involvement of students, faculty members, and administrators in the design and development of each UWW unit. It is clear that students are less resistant to programs they themselves have helped to devise and operate.

3. Development of special seminars and other procedures to prepare students to learn on their own and . . . to prepare faculty members for the new instructional procedures to be used in the UWW program.

4. Employment of flexible time units, as no two students are exactly alike in their background, educational aptitudes, interests and needs . . .[In what is otherwise almost a verbatim recount of Baskin’s and Hallenbeck’s list, a publication entitled UWW: First Year Report [9, p. 9] adds the following sentences to this item: ‘Programs were to be individually tailored by student and advisor. There would be no fixed curriculum and no uniform time schedule for the award of the degree.’]

5. Use of a broad array of resources for teaching and learning, both in and out of the classroom, recognizing that students also learn from their own firsthand experiences.

6. Use of an adjunct faculty involving many persons outside the regular educational institution who can contribute significantly to students’ undergraduate experience . . . Any society should include among its educators its best artists, scientists, writers, musicians, dancers, physicians, lawyers, industrialists, financiers, and other specialists.

7. Opportunities for students to use the resources of other UWW units in the network. . . In addition, learning may be greatly enhanced if a student can be part of the ‘mix’ of more than one educational institution.

8. Traditional assessment procedures (time spent in classrooms, course credits, grades, achievement tests on prescribed subject matter) do not reveal enough about the individual’s growth and development . . . One crucial task of the UWW program will be to find new approaches to evaluation that will periodically appraise the individual’s cognitive and affective learning for the student and his advisor.[xiii]

Unfortunately by the mid-1970s the UWW movement had lost support, perhaps driven out of business by low-cost Community Colleges, and cost tightening issues. Montieth College closed in 1972. The UWW was an idea that could quickly bend and mold to the educational needs of its students. Its history and methodology in education has almost vanished, replaced by cookie-cutter, degree-focused colleges and “cost-efficient” learning. There is cause for re-examining the UWW and Free Universities, a need for reintroducing policies and experiential teaching methods which are more in line with the cognitive needs of students, reaching out to the student as a respected human element in the teaching process.

COMMUNITY FREE UNIVERSITY OF DETROIT

In 1968 another Free University would appear in connection to Wayne State University. Inspired by the Free University movement in New York and in San Francisco. A group of students began the school, grouped around Paul Brians, a young English professor at Wayne State. He was not familiar with the Artist Workshop and its earlier experiment at free education. While researching the Free University movement I came across his website which contained a brief history of the Community Free University of Detroit, it is reprinted with his permission:

“A group of WSU students from the local YMCA came back from a meeting in Portland on alternative education fired up to do something similar in Pullman. They knew of me as a young faculty activist, and asked me to join them in organizing this new enterprise. We met at Betty’s Tavern (now My Office) late in the fall of 1968, and quickly arrived at a vision CFU has essentially adhered to ever since. We would let anyone teach anything to anyone so long as the content wasn’t positively illegal. The fee for a course would be a minimal one dollar. No exams, no requirements, and–most significant of all–no pay for the teachers. This was to be a strictly volunteer effort.

There are no copies of the first Free U. catalogue in my files, but I remember it vividly because we mimeographed it, assembled it by hand, and stapled it together in a long, hard session on the CUB 3rd floor. We put out press releases and stuck up posters. The time was right: before we were ready to begin registration that spring of 1969, there were over 500 people waiting in line, hoping to get into fewer than a dozen classes.

The Free U roared ahead during the late sixties and early seventies, at one point offering fifty courses in a single semester. It was normal to have four or five hundred students sign up for classes. After several years, we decided to offer a summer session as well (which is why the number of years we’ve been in existence doesn’t divide neatly into the number of semesters). One summer Mount St. Helens threatened to defeat us, but we came out with a small catalogue anyway.

One of the things that made alternative publications and institutions possible was cheap web-press printing. We could print and distribute by hand thousands of flyers printed for us at local newspaper plants, all paid for out of the dollar each our students paid us. One of our biggest problems over the years has been the escalating cost of newsprint and printing. It was a severe blow when the Daily News decided not to do small print jobs any more and we had to turn to a much more expensive format (these flyers cost more than ten cents each) and print many fewer copies. I have to give them credit for unfailingly printing our press releases, however. Even when we couldn’t afford to buy ads, their pages were open to us, which is more than can be said of the Daily Evergreen, which steadfastly ignored the Free U. throughout almost all its existence, despite our many efforts to get coverage in its pages.

CFU has offered an extreme variety of courses: early examples were radical economics courses, horse-race handicapping, and witchcraft. We taught people how to tune up their VW engines and cook classic French cuisine. Our hallmark was openness to all comers: we several times listed courses taught by religious fundamentalists alongside courses by groups aimed at combating those very fundamentalists–and got the warm support of both (though I can’t say we generated many enrollments for either side).

Very few of our instructors were professional educators. They have been mostly people who had a skill or interest they wanted to share for the pure joy of it. Many of have been retired people–CFU has attracted teachers of all ages from the beginning. Some of them tried out their wings in our low-risk environment and went on to become paid teachers in other programs. Some businesses reached out to their customers through the Free U., notably Doug Eier’s bicycle shop, which taught many folks how to fix their own bikes. Doug also led many biking, rafting and skiing expeditions.

We are proud of the fact that many ongoing organizations and projects were incubated in the Free U. The first gay group at WSU, the first Marxism study group, the first Aikido club, and many other organizations and groups debuted as CFU classes.

CFU has never had a physical educational plant, offering classes mostly in church basements (until the churches began to charge for their use), the Cougar Depot, people’s living rooms, and other odd spots around town (we rarely held classes on the WSU campus, since we resisted the controls implied by official university recognition); but in so far as there has been a building identified with CFU, it has been the Common Ministry’s always-hospitable Koinonia House. We also owe a debt to Neill Public Library in Pullman, where our brochures always landed first and were always available. They’ve been great supporters over the years.”[xiv]

Although its origin was open-ended and undefined, the Free University was still a system, one formulated on change and freedom. Its weakness should not be looked at as what to be avoided in education, rather its functionality and break-up was a natural consequence of evolution and learning inside any free educational system. The Free University movement left many useful ideas in its wake. Its a large subject in need of study, especially as present systems in creative arts education are failing; in need of ways to stay energized and viable.

–Cary Loren, 2004

Notes:

[i] A comprehensive history is presented in Robrt E. Weir’s Beyond the Veil: The Culture of the Knights of Labor (Penn. University Press, 1996)

[ii] Joseph Labadie, Anarchism: What It Is and What It Is Not, online article at: http://tmh.floonet.net/articles/anar_jal.shtml A full-length biography, All-American Anarchist: Joseph A. Labadie and the Labor Movement, by Labadie’s granddaughter, Carlotta Anderson, was published by Wayne State University Press, Detroit in 1998. http://recollectionbooks.com/bleed/Encyclopedia/LabadieJoseph.htm

[iii] Charles Olson, to John Sinclair and Robin Eichele, Western Union Telegram, Gloucester, Mass., 1/19/66 Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[iv] John Sinclair, ‘Human Universe: The Work of Charles Olson’ unpublished mss., Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan. nd,np. (1966)

[v] Sinclair, Ibid.

[vi] Undated flyer produced by the Artists Workshop.

[vii] ‘The Free University of Detroit, Winter-Spring Term 1966, Catalog and Class Schedule’, (Free University/Artists Workshop Press, Detroit, 1966) pp. 2-3.

[viii] Peggy Cronin, ‘Free University of Detroit Founded by Artists’ in the Daily Collegian, January 24, 1966, p. 5.

[ix] Ibid., p. 5.

[x] Ibid., p. 5.

[xi] George Walker, ‘New School’s Creed: Think As You Like’ Detroit Free Press, April 1, 1966, p. 3, section A.

[xii] Michael McClure, ‘Poisoned Wheat’ in Work #4, (Artists’ Workshop Press, Detroit, 1966), np

[xiii] See Rick Hendra and Ed Harris paper: “Unpublished Results: The University Without Walls Experiment” http://www-unix.oit.umass.edu/~hendra/Unpublished%20Results.html

[xiv] Paul Brians, ‘History of the Community Free University’ http://www.wsu.edu/~brians/cfu.html

Tags: Cary Loren, Education, Essays, Free University of Detroit, Monteith