James Semark – A Metaphor for Charles Moore

“Detroit is one place where you can be both famous and broke at the same time!”

– Marcus Belgrave

I believe this about Detroit: if everything would be taken away from the community – the cement, the steel, factories, automobiles, assembly lines, etc. – what would remain would be a form of supercharged cultural expression – music like what was made in the Artists Workshop four decades ago. For those who were not there when the sound was alive, I can best describe it in three aspects:

- Dynamic – high-energy. The music blew you away every time you encountered it.

- Unique. The music bore the stamp of “we invented it.”

- Warmth and depth. A feeling, a passion about making the music. Neither cold nor shallow.

These qualities define the Workshop style. More than a “Detroit sound” – it’s a high-vibration feeling – one that occurs in the moment. No media can accurately reproduce the experience. The music is so dynamic and powerful that, if you’re not ready for it – it sends you packing in another direction.

- Time travel to the mid-sixties: in the older bebop style, one of the principles is to “play time.” Then, alternative communities popping up everywhere: New York – San Francisco – Chicago – Detroit. To those of us inside the counter-culture, we move away from bebop rhythm to a newer perception of time – we call it “pulse music,” or simply, “free jazz.”

- Fast forward to the amphitheater, Ann Arbor: the Artists Workshop Music Ensemble standing behind the band shell. Someone asks, “What are we gonna play?” The man of the moment is Charles Moore. He says, “Let’s play something in ‘D’” – and they go out. Lyman Woodard on organ. Charles on cornet. Ronnie Johnson on drums. John Dana on bass. The other reeds and brass. They make it up as they play.

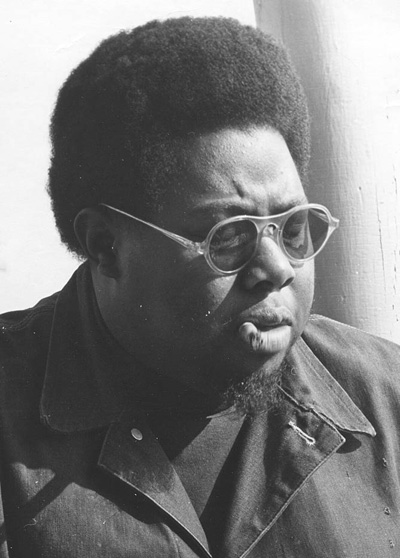

Focus on 1965: No history now, just metaphor: the sound of Charles Moore puts its stamp on the whole era. Many great musicians come and go out of the Detroit Artists Workshop. Charles is leader – shows the way. Parallel to another cornetist who defined the Chicago sound forty years earlier. Charles’ music is jazz history – not the up-the-river thing, but the story of freedom. Free with so much fire. The effect of tones makes the difference – it’s how hard you blow them, twist them – the tones are tunes blown back against brick walls. Draw parallel to another trumpet player who defined the New York sound twenty years earlier. The tones glide, bounce off floor and walls – make you listen. The energy so thick it cuts you in half. The pulse so heavy you feel the perspiration. The pulse stays with you all the way to next century. No history now – you are there in the moment. My parallel. My metaphor. Recordings to listen to, with the caveat: nothing comes close to being there in the experience, in the music as it was played.

First music clip: Charles Moore solo – full of melodic invention – phrases leaping and soaring. Touch of fiery texture here and there – touch of blues tonality. Charles invents his own theme, varies it, reintroduces it. The band is the Detroit Contemporary Five (with guest pianist), Lansing, Michigan, 1965. Charles Moore cornet. Pierre Rochon trumpet. Ron English guitar. John Dana bass. Danny Spencer drums (and unidentified pianist) – see Leni’s photo for the DC5.

Second clip: Charles Moore’s solo in the middle of Chorale for the Splivey Hotel, my work. Performed by the Artists Workshop Music Ensemble during the DeRoy Auditorium concert, November, 1965 – again, see Leni’s photo. Charles in an up-tempo groove. Powered by the multi-dimensional drumming of Ronnie Johnson. Driving bass of John Dana. This is a high point for Charles – for me, too. The ensemble rises to the occasion – I mean, they EXPLODE – the result is far beyond what I, or anyone else, expect. Fortunately, a recording survives.

To sum it up: the music is high-level energy. It is original. It has passion. If you are there when the music is made, then the sounds resound off you – you are a participant. You are as necessary to the music as the tones are – this is a community experience. I’m glad to share these recordings with other people after forty years. Will you hear them?

James Semark, January, 2004